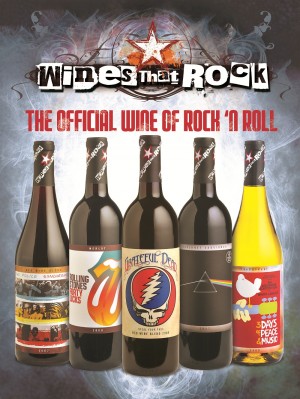

Wines That Rock: A Robust Revolution in Taste

GALO: The debate over wine as a commercial product or as art can be very polarizing, but there are also many who classify it as dichotomous. Obviously, Wines that Rock emphasizes it as artistic, but what are your thoughts on commercialism? Is it something that dilutes the art of winemaking?

MB: It depends upon the winemaker and how far they allow commercialism to drive them. There are winemakers whose goal is to seduce the palate of an influential wine-writer, get a high score in their influential publication, and thus, drive sales of their wine. This is where commercialism steals the soul of the wine and its maker. Too little commercialism and you might not sell any wine though. You do need to get word out there somehow.

GALO: In thinking of wine as art, there is the traditional French terroir idea dissecting the method in which climate, geology, and vineyard are expressed through wine. Do you take this idea solely under consideration in creating Wines That Rock, or are you excited about intervening in the winemaking process to change the wine’s flavor to fit a certain taste? Do you favor innovation over tradition?

MB: Terroir certainly exists and expresses itself in the wines we make in Mendocino. I am a “terroirist” and believe that a winemaker can either suppress or preserve the character of the land in their wines through their level of intervention. No intervention at all results in making vinegar. Too much intervention leads to a soda pop beverage that may be consistent, but is not really wine. I believe my responsibility is to nudge and encourage the wines evolution, but not be overly forceful or manipulative in that role. A midwife would be a good analogy. Once the wines have completed fermentation and are more or less set, it is then where the art of blending allows me to see what combinations of unique features from different wines results in the style of wine I am looking for. It would be foolish and arrogant to think that technology can create more diversity than nature. Besides would you rather drink milk made by machines or by a cow?

GALO: If you believe in human intervention in winemaking, how do you feel about winemakers being called artists or are they just stewards in the process?

MB: I think it is difficult to say if it is one or the other since there is a degree of art in stewardship. But a simple answer could be that we are stewards in the process of making wine and the artists in blending wine.

GALO: If you let your imagination run away, and fantastically envision what would happen if a bottle of Wines that Rock could talk, what do you think it would say about the winemaker, your milieu or style?

MB: The egoist in me hopes that they would all pour me a glass and say how great I was at organizing their individual talents into one cohesive unit. But the reality would probably be in seeing them all yell something unpleasant at me for all the “retakes in the studio” that I put them through in the repetitive blending process.

GALO: With creating the 2009 Rolling Stones Forty Licks Merlot, you again came up with an unconventional mixture: Black cherry, plum, brown sugar, cinnamon and cedar, with a hint of mint. What is the perfect meal to complement that peculiar blend, and how did you find it?

MB: Rosemary encrusted pork tenderloin with a light plum reduction sauce if you are in a formal mood. BBQ hickory ribs if you are outdoors and playing the music loud. I play around in the kitchen and drink wine while I prepare. This match just sort of found itself.

GALO: With your 2010 Woodstock Chardonnay as an ode to the famous Woodstock festival, you created what you call a “naked” wine, which was not “dressed up” with oak or malolactic fermentation, as to create that signature muted flavor of most Chardonnays made in other regions. In that aspect, the wine speaks to the “individual expression and breaking from the past” messages of Woodstock, but what about the wine is symbolic of the festival’s community message of the collective notion of joining in together?

MB: The communal aspect of the festival is something that exists in the wine community of Mendocino that you catch in glimpses only in other more well-known wine regions. We regularly trade equipment, such as the pump we loaned our neighbor the other day when theirs failed. We actually get along and share ideas and encourage one another out here. There is a sense of togetherness that exists in Mendocino’s wine region that matches what Woodstock managed to become known for. The Woodstock Chardonnay is from a blend of community family farmers fruit all within a 15 mile radius of the winery it is made at. We see these farmers often and the wine is very much a testament to them.

GALO: The bottles’ musical artwork evokes this sentimentality aspect, which was greatly seen in Pablo Picasso’s Cubism works. What is the purpose for creating this sentiment in tying wine to rock ‘n’ roll nostalgia, and what meaning, if any, are you trying to convey with it?

MB: Compared to wine, Picasso’s sentimental reach seemed a bit melancholy in its scope from my perspective. While these wines and their imagery will certainly stir memories from the past, they are best consumed and enjoyed in a way that creates new memories with friends, lovers, and family. I see that the wine and music combination can serve as a catalyst to fun conversation and interaction rather than just reflection.

(Article contined on next page)