Chasing Memory with a Camera

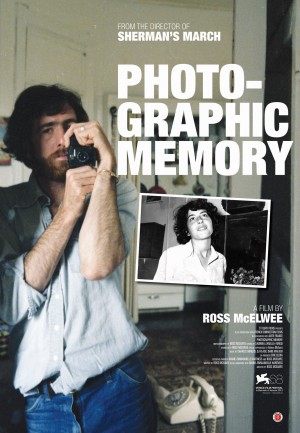

Chasing one’s memories down the decades is a little like trying to catch butterflies in a snowstorm. You know they’re there — if you’re patient enough, persistent enough, you’re sure to capture something, but what? In Ross McElwee’s elusive documentary, Photographic Memory, we see a middle-aged man trying to do just that. Whether focusing his lens on his teenage son, or traveling back to a small town in Brittany, France where he left a first employer and a budding love affair in his youth, it’s a frustrating, occasionally fruitful journey at best. At its worst, it’s an often exhausting and self-serving sojourn for the viewer.

The film opens on an early boxing match between two children — McElwee’s son Adrian and his little sister Mariah. Within seconds, McElwee’s own narrative voice sets the tone, a subjective and slow-paced confessional that describes for us what he is thinking and feeling about what we see. We find out soon enough that Adrian is a major player in this meandering odyssey. We are told that the boy “always liked being filmed.” Perhaps, we can believe that statement when he is brushing his teeth at age 10, while mugging for the camera, but it’s harder to buy when the subject is a sullen, expressionless teenager who simply wants to be left alone with his own laptop obsessions.

Adrian is seen in his senior year, having moved into his father’s apartment where dad feels the atmosphere will be conducive to studying — Adrian instead, not surprisingly, blows off his schoolwork. Dad is there, video camera in hand, questioning his son’s every motive, holding the shot for interminable moments on this unresponsive person to the point that we as the viewers almost expect the young man to suddenly rise up and hurl himself at this artificial, unwanted eye. A very telling moment occurs when McElwee shows an earlier clip of his own father, a successful surgeon at work, who chides his son by facing the camera and stating that “I’ll be glad when that big eye is gone.”

One of the few saving graces of the film is McElwee’s own self-deprecation. He is not afraid to confront such judgments directed at his person, whether from a family member or a friend or stranger. As a professed cinéma vérité director, he studied under documentarians Richard Leacock and Ed Pincus, both pioneers of that movement. “It was a new way of making films,” he has admitted, “to eliminate the film crew. You lose some technical polish, but it’s much more intimate and less intimidating to your subjects. It allows you to shoot with the autonomy and flexibility of a photojournalist.”

Of course, McElwee’s reliance on “simpler tools” is one of the key factors that drive a wedge between himself and Adrian. How can they communicate over this chasm created by technology? We can feel the hard slap of Adrian’s rejection. After all, his father doesn’t even have a Mac.

It’s important to remember that McElwee himself is a victim of technology — the world of the printed image. If the speed of reception is different, the act of lingering for innumerable minutes over one image caught is its own trap. What to believe in what we see? American writer and filmmaker Susan Sontag, in On Photography, a profound investigation of what we should expect from the image, had this to say: “Photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe.” Has McElwee invaded a barrier between himself and his son that can never be mended?

These interludes with Adrian are thankfully broken up by McElwee’s journey back to Saint-Quay-Portrieux in Brittany, for the first time in decades. He mulls over proof sheets and illustrated journals from the year he lived here, assisting a wedding photographer named Maurice. He was fired eventually, for losing negatives. Where is the man now? And Maud, tending the local market, the girl whose photo he has kept in his wallet all these many years. Would he have ever become acquainted with her, if she’d been texting on her cell phone instead of stroking the ears of a rabbit in her lap?

We move along, at a snail’s pace, as McElwee continues his search. Black and white stills are interspersed from McElwee’s fledgling attempts at art photography — viewing the distant horizon through a half-filled wine glass, or a remembered café. He tells us what he thinks it was like to be in his 20s. Stumbling into this long ago village was like stumbling into the most exotic place on earth. Everything is the first time. Such musings can try our patience. There must be a faster way to get where we’re going; it is, after all, a film. Yet there is a truth we can all recognize here. Everyone is or was young once. If our filmmaker can just get back there, maybe he’ll understand his own son better.

An aging architect remembers the photo shop, eventually helping him unearth Maurice’s widow. McElwee hires a driver, retracing some of the villages he traveled to while working with Maurice. A bit of fresh air enters the scene — tracking the storefronts, sharing impressions with a local photographer, observing a small bulldog in an open-air market licking the ankles of a customer. Finally, we breathe a sigh of relief as the widow Helene enters the picture.

She’s a bit wary, but polite, even warm, in a French bourgeois kind of way. More importantly, she’s a real-life woman for our narrator to interact with, willing to share her own box of pictures, of unresolved memories and mysteries about Maurice with him. McElwee still functions surprisingly well with his French, and Helene is more than willing to speak with enough clarity that even those of us with a rudimentary familiarity with the language can get along just fine with a willing ear and helpful subtitles. Offering to act as a Watson to his Sherlock Holmes, she offers to make calls, to help him find the all-important Maud.

When Maud at last appears, she hardly matches the photo in McElwee’s wallet. But how could she? Almost four decades have passed since their affair and she wears the ravages of time on her sleeve. But she wears them with pride. There’s a no-nonsense confrontational quality about her, a salt-of-the-earth humor mixed with cynicism reminiscent of the incomparable French actress Simone Signoret. She tells him she’s the same girl — in her mind. She fries up frogs legs and at one point, orders him to shut off the camera. It is in these exchanges, with Helene and the older Maud, that McElwee demonstrates what true cinéma vérité can do at its best. For the viewer, it’s been a long wait.

McElwee has been teaching filmmaking at Harvard University since 1986, where he is a professor in the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies. Born and raised in North Carolina, he is a quintessentially American documentary filmmaker, known for his autobiographical films about family and personal life. He often weaves the highly personal story with an episodic journey, mixing his own introspection with a historic parallelism. Such films as Sherman’s March won numerous awards, including Best Documentary at the Sundance Film Festival. It was also cited by the National Board of Film Critics as one of the five best films of 1986. Most of his films were shot in his homeland of the American South, among them the critically acclaimed Time Indefinite, Six O’Clock News, and Bright Leaves.

There’s a memorable final scene in Photographic Memory, where a very young Adrian is pictured on the beach, intently digging a large hole in the sand. When McElwee asks him what he is doing, he confesses (in that profound way that children can sometimes do when least expected) that he is looking for “the deep surprise of the ocean. You never know what you’ll catch.”

McElwee, the filmmaker and the man, is on the same quest for the deep surprise. It’s up to his viewers to decide whether they want to invest the time and patience to come along.

(Ross McElwee’s Newest Documentary, “Photographic Memory,” is on view at the IFC Center at 323 Sixth Avenue, New York, NY 10014. For more information or tickets call 212-924-7771 or visit http://www.ifccenter.com or http://firstrunfeatures.com.)

Rating: 2 out of 4 stars