Nat Hentoff: The Man Who Writes Jazz

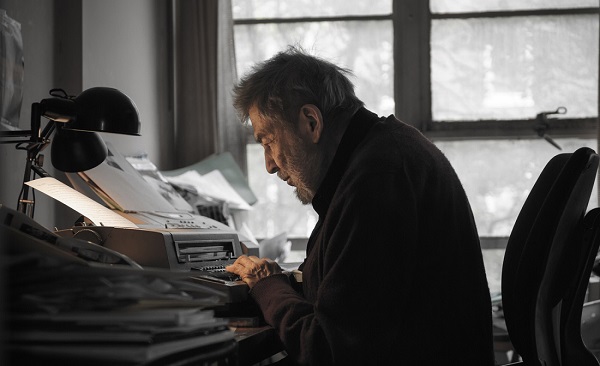

Nat Hentoff at work in his office in Greenwich Village, 2010, as seen in David L. Lewis’ documentary “The Pleasures of Being out of Step: Notes on the Life of Nat Hentoff.” A First Run Features release. Photo Credit: David L. Lewis.

It’s ironic that the man who has said the most about jazz in our culture doesn’t say it with a horn or a snare drum or on the ivory keys. He doesn’t even keep the beat with his feet. In fact, Nat Hentoff has been out of step and happy about it for decades. With two fingers to his typewriter keys, he has reported just about everything worth saying about the art form and the First Amendment for over seven decades.

That’s right. A byline by Hentoff not only guaranteed an inside view of the coolest players in jazz past and present but also an incisive and often controversial view on our rights as Americans. “We have jazz,” he says, “because we’re a free people — using the First Amendment like James Madison and the rest of those improvisers.” In David L. Lewis’ no-holds-barred documentary, The Pleasures of Being Out of Step, Notes on the Life of Nat Hentoff, we get a perfect match between director and subject. Lewis is a veteran New York City journalist with 30 years of experience in print and broadcast media. As a seasoned news writer, he brings a special understanding to the question of how Hentoff became Hentoff, and how it all began.

We hear about the nine-year-old Boston boy who first heard the notes of Artie Shaw’s “Nightmare” wafting into the streets from Krey’s Music Shop. The sounds were life-transforming. Already familiar with the cantorial one-syllable improvisations of Yiddish music, he could later recognize what he called “the cry” in the best of modern jazz. Sleuthing for answers among the trumpet sounds of Miles Davis and the tenor sax of John Coltrane, he could say about Coltrane that “there is a cry, not necessarily a man’s and that cry Coltrane has.”

After a stint at Northeastern University, he hosted a radio show while pursuing graduate studies at Harvard. A Fulbright Fellowship at the Sorbonne was followed by four years as an associate editor at Down Beat magazine, and it was there that he cut his wisdom teeth in jazz journalism. As jazz historian Stanley Crouch tells it, he first met Hentoff on the back of an album. He had never read liner notes of that quality before. Here’s Hentoff’s assessment of Charles Mingus: “Mingus tries harder than anyone I know to walk naked — he’s unsparing of phoniness and pomposity and is hardest of all on himself if he feels he’s conned himself in any respect.”

Before his encounter with Hentoff’s views, Crouch believed such descriptions by other copywriters were “sophomoric” at best. Perhaps the biggest fan of Hentoff’s album notes — essays really about the art — is Dan Morgenstern of the Institute of Jazz Studies, who walks us through the aisles of legendary albums and lovingly pulls out several for our inspection.

The occasional samplings of Hentoff’s prose are seamlessly narrated by Andre Braugher and show the writer’s love for his subjects. About Miles Davis’ incomparable Sketches of Spain, Hentoff sees it “as a measure of Miles’ stature as a musician and a human being that he can so absorb the language of a culture that he can express through it a universal emotion with an authenticity that is neither strained nor condescending.” It was the feeling that counted. And what would a documentary about such an unrelenting jazz enthusiast be without some of the music that inspired him?

While he was co-editor of Jazz Review from 1958 to 1961, and worked for the Candid label as an A&R director, he produced recording sessions with favorites like Charlie Mingus, Cecil Taylor, and Abbey Lincoln. We get archival performance sessions or interview clips not only of those three but Billie Holiday, Max Roach, Duke Ellington, and many others. Of course, we want more. Maybe that’s the nature of jazz in the hands of the greats. But then the focus would be elsewhere and Hentoff is the focus, after all.

And that’s the problem and the solution in one. A series of current interviews and close-up glimpses give us the man as he is today — frail, soft-spoken and innately shy. In some respects, he’s a shadow of his former self. This is not to be critical of an individual who has let us be privy to his most revered beliefs and has proven himself as a chronicler of our musical heritage many times over. But the ravages of time can be painful to watch. Thankfully, Hentoff’s subjects and the individuals on the sidelines who knew him best never cease to fascinate, and in the final analysis, that saves the film.

One of the pleasures of watching such a healthy mix of archival footage is observing a younger and more intense Hentoff gaining the trust of the likes of Max Roach, who we are told made lists of many people he didn’t like. But he liked Hentoff. Maybe they respected each other’s passions and idiosyncrasies. Roach confessed about his music that “what we do is like the Constitution. It’s a lot of individuals with individual voices really listening to one another and coming out with a whole.”

Hentoff’s hookups with the jazz world were always paramount but his fascination with Bob Dylan and his “talking blues,” Lenny Bruce and his uncensored mouth, and even Malcolm X are all touched upon. The segments on Bruce are particularly telling — it’s hard to witness such a brilliant mind dissolving in front of our eyes — a man in conflict with an ongoing dependency on drugs.

His purest passion, however, was the First Amendment. He was determined to put himself in the center of controversy whatever the cost. As a Boston city reporter in the ’40s, he learned his lessons well from his boss, Frances Sweeney. “She taught you the pleasures of being out of step. You don’t have to worry about being in step,” he warned about the dangers of political correctness and what it can do to diminish the individual.

One of his greatest battles was defending the right of Nazi sympathizers to march in Skokie, Illinois in November of 1977. One woman, a young 16-year-old girl at the time — totally at sea as to why a Jewish man of her own faith would defend the right of these neo-Nazis to march — tells about the eloquent, well-thought-out letter she received from him. It was an awakening to her about what the First Amendment really meant. The historic clips are helpful, but such a highly personal interview like this one is a welcome surprise.

Hentoff’s wife Margot is an outspoken presence about her husband’s absolutism. She’s a delightful addition to the film and it’s easy to see that the chemistry was immediate. She even admits her continual amazement with a famous spouse that held “the humble idea that no one knows who he is.” There may be regrettably some truth to that today with a younger, less informed audience. How can they make sense of the fierce passions that first fueled jazz and civil rights? Footage of a Walgreens luncheonette uprising between blacks and whites may not register with the under 30 crowd but it’s an attempt, however brief, to remind the rest of us of an earlier, less forgiving time.

There’s enough footage interspersed in the unfolding story to give us an idea of the heady counterculture time these two inhabited. With two children apiece from prior unions, they eventually had two of their own, but when Margot was unhappy about an early pregnancy, she went across the border for an abortion. Hentoff had always been against war, against capital punishment, and after researching the advances in fetal surgery, he became an adamant pro-lifer. When confronted in a brief televised clip by Anna Quindlen (an early spokeswoman for women’s rights) about abortion, she said she couldn’t understand how he would defend her right to privacy in her own home but not the privacy in her own skin. He listens but it’s easy to see he’s not about to change his views.

Another rival was Karen Durbin, his then publisher at The Village Voice. She doesn’t mince words about their bombastic arguments and his odd man out position during the AIDS crisis and other issues where she felt he had adopted “certain lines of social conservatism.” When Hentoff was ultimately fired from the paper after a decades-long association, it sent a shockwave through the publishing world. It was like cutting off a major limb of this very public organ of alternative journalism. Tony Ortega, the Voice’s publisher in 2008, defends his action in light of the new demands of turning out a digital daily as well as a weekly newspaper.

But as the film’s end commentary attests, the man is “still writing everyday and still pissing people off.” As Hentoff says, “At least I know who I am when I write.” He’s the author of 20 non-fiction books, nine novels, and two memoirs. His writing has been published in Down Beat, The Village Voice, The New Yorker, Jazz Times, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Playboy, Esquire, The Atlantic, The Progressive, and The New Republic.

And there’s more. Hentoff was the first nonmusician to be named a “jazz master” by The National Endowment of the Arts. His role was indispensable — pioneering jazz as an emerging art form while serving as a founding father for “alternative” journalism.

Thanks not only to the prodigious efforts of director Lewis but the award-winning cinematography of Tom Hurwitz, this is one man’s story writ large, a kind of phantasmagoria of art and activism played out like a hypnotic riff, inviting us along on the journey.

Rating: 4 out of 4 stars

“The Pleasures of Being Out of Step” opens in New York at the IFC on June 25 and at Laemmle Theatres in Los Angeles on July 4th. It has a run-time of 86-minutes. David L. Lewis’ companion book to the documentary, “The Pleasures of Being Out of Step: Nat Hentoff’s Life in Journalism, Jazz and the First Amendment” is now available in paperback from CUNY Journalism Press.

Video courtesy of First Run Features.