‘Joffrey’: Ballet Mavericks Making a Difference

Lithe dancers from one of America’s premier ballet companies twirl and leap, their technique top-notch, their extended limbs seemingly reaching the heavens. But instead of the expected Stravinsky or Tchaikovsky playing in the background, Prince’s “Trust” blares, replete with synthesizers and pounding drums. There’s not a tutu in sight: these ballet dancers wear glittery gold or hot pink bodysuits, and the audience goes crazy for them, jumping up and clapping along. Welcome to the Joffrey Ballet, as seen in the documentary, Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance.

In 1956, Robert Joffrey and Gerald Arpino founded a company destined to change the way the world thought about what ballet could do. They longed to create a uniquely American group, different from the most highly regarded companies of the time, which tended to focus with laser-like precision on the classical in both body and repertoire. The Joffrey Ballet made political statements, performed psychedelic rock ballets as well as traditional ones, and accepted dancers who didn’t fit the typical mode because of height, skin color, or, as Joffrey biographer Sasha Anawalt put it, “big breasts.”

More than 50 years after the company’s humble beginnings, producers and longtime Joffrey fans Harold Ramis and Jay Alix decided the time had come to tell the story of the visionaries who turned the classical world on its ear. They teamed up with award-winning writer and director Bob Hercules and, for narration, borrowed the voice of Mandy Patinkin, the venerable Broadway actor, perhaps most famously known as The Princess Bride’s vengeance-seeking Inigo Montoya. The resulting documentary, premiering in New York City’s Cinema Village on April 27th with special guest appearances, and due out for wide release on DVD in June of this year, often leans oddly toward the conventional in its ode to a groundbreaking company. Ultimately, however, it provides some moments of exhilaration that may remain forever etched on your eyelids.

Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance touches on the company’s initial rise, with a tiny group of dancers touring the country in a station wagon and performing in high schools, then journeys on to the seemingly insurmountable setback when a jealous sponsor of the company decided to hire away all of its dancers for her own fledgling group. Hercules shows how, over the ensuing decades, the country watched the company build itself up again, enjoying massive successes while weathering storms like Joffrey’s death from AIDS and a disorienting, but ultimately rewarding, move from New York City to Chicago, where it currently thrives.

In part because the company has both broken so much new ground and endured so many hardships over the last 50-odd years, the 80-minute documentary moves at a breakneck pace, barely surfacing for air. The film spends roughly two minutes on Joffrey and Arpino’s backgrounds, even though the potential exists to mine much of interest from their origins. The viewer knows that, as a young boy and the son of two immigrants from vastly different cultures, Joffrey loved the ballet. But there’s no explanation of why he loved it and what aspect of the dance touched some deep part of him, pulling him into its powerful orbit. Similarly, Patinkin narrates that the two men were introduced by a vague “family connection” when Joffrey was 16 and Arpino, 22, at which point the latter had never even seen a ballet. But the film doesn’t explore the implications of coming to ballet so belatedly, and only clarifies much later in passing that the two men were lovers. This unwillingness to linger contributes to an editing and formatting style that could, for the most part, come straight from a guidebook entitled “How to Make a Perfectly Standard, Slightly Perfunctory Documentary.” It seems a strange fit for subject matter that prides itself on pushing boundaries.

Still, despite these quibbles, it’s near impossible to go wrong when you have access to the spectacular dance footage with which the filmmakers liberally sprinkle the proceedings. The camera captures the animation of the company’s performances, from the early classical-leaning ones to the adventurous productions that came later. What remains steady throughout is the quality of the dancing: the ease with which the dancers seem to spin forever in complete synchronism, the total commitment with which they thrust their fists or their hips, and how they seem ready to burst with defiance or desire.

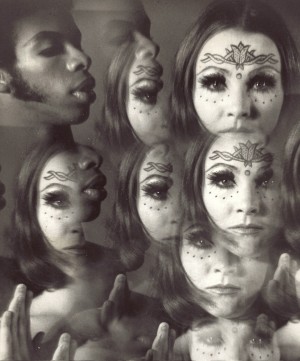

Perhaps the most wonderful part comes from watching the talking head interviews with former dancers who speak eloquently about their experiences with the company, and then getting to watch those same dancers, 30 or 40 or 50 years earlier, dancing with joy and vigor. Trinette Singleton, who started training with Joffrey in 1965, comes across as composed until she starts discussing Astarte, the hallucinogenic multimedia ballet in which she starred. Singleton begins to shake as she recalls her nerves, her face shines with fervor, and suddenly the film is back in 1967. Barely out of high school, Singleton manages to be both majestic and touchingly innocent, her eyes wide and searching as she spreads her arms in imitation of the titular Babylonian goddess. She’s luminous, and the film lights up with her.

Hercules also completely nails the Joffrey Ballet’s uniquely American aspect. In interviews, the dancers evoke the shock and heartache they felt upon learning of JFK’s assassination as they toured Russia. They remember wondering what they were doing “flitting around on [their] toes” when news of Vietnam and Kent State reached them, and then channeling that anguish into political pieces. The AIDS epidemic knocked persistently on the company’s door in the 1980s, altering it forever, and those interviewed can’t keep themselves from crying as they talk about it. The documentary shows that the changes and revolutions occurring all over the country wove themselves into the company’s history, reinforcing Joffrey’s goal to create something truly American.

The film transcends conversation about dance in and of itself to demonstrate how dance interacts with the outside world and becomes better, more thrilling, and meaningful. Viewers might wish that the people behind the film had made some more maverick decisions themselves, but not everyone can be as daring as Bob Joffrey and Gerald Arpino. Maybe exposing the world to their incredible work is enough.

Rating: 3 out of 4 stars

“Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance” will be screened at New York’s Cinema Village, located at 22 East 12th Street, New York, NY 10003, on Friday, April 27, 2012 for a one-week limited engagement with special guest appearances during the opening weekend. For more information on the New York City screening or screenings in your area, visit http://www.joffreymovie.com.