‘Massacre (Sing to Your Children)’: A Psychological Mix of Promising Charm and Tangled Mess

Political theater is almost always problematic. Characters often get lost in the messages they are trying to get across and the messages then feel incomplete or didactic. Massacre (Sing to Your Children), currently playing at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater in New York City and directed by the well-known Brian Mertes, whose acclaimed works range from theatre productions as well as TV series inclusive of the 1952 show Guiding Light, is a play full of political messages, as well as bizarre human interactions, and enough blood for a slasher film. It centers on a group of odd people in a small New Hampshire town who plot — and seemingly succeed — in killing a controlling, meddling, and murdering neighbor named (for simplicity’s sake) Joe. As they confront the consequences of their act, they begin to confront themselves and each other; thus the play unfolds.

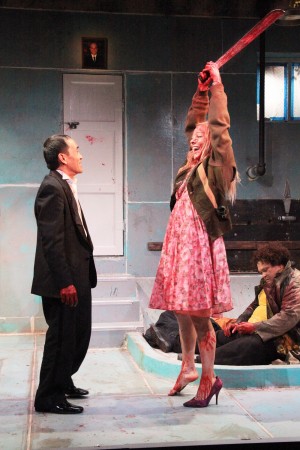

The scene is a drab, empty cellar that looks like it might have been a torture chamber. As the lights go up, blood-covered people literally explode into it, through windows, trap doors, whatever opening through which they can fit. They are in a state of exhilaration and fear, like children who have gotten away with something forbidden but might still get caught. Gradually, it comes to light that they have finally “gotten rid of him,” the “him” being Joe, who they characterize as a rapist, a child molester, a small town political dictator — Joe carries the blame for anything that has happened to them or their town. They ceremoniously remove a photo of Joe from above the front door; the photo had hung there like pictures of heads of state hang the world over.

But as they wash off the blood, the truth begins to emerge: Vivi, the hot town schoolteacher, lured Joe to his death by going on a fake date with him; Vivi has been in love with Panama, the ringleader of the murder, since childhood, but he married someone else whose death he incessantly mourns. The married couple, Erik and Janis, seem overly fond of each other, but may also be hiding a secret that only gets hinted at; Hector, the town diner proprietor, is the resident homosexual, also in love with Panama, and blames Joe for the disappearance of his only son, conceived one errant night with a woman. Elisio, a young black man, is all brawn and brashness, happy that Joe is gone and happy not to be in his native Chicago; his white girlfriend, Lila, is a psychic who has lived with her mother for years and avoided life; she also dated Joe and is very quiet about it. The fight among themselves crescendos as to whether Joe is truly dead or not, and through the first act they wind themselves into a frenzy, everyone suspicious of everyone else. Until there is a loud knock at the door and the lights go down.

Joe appears in the second act — no, he isn’t dead, but it’s doubtful he was ever truly alive either. He is a dapper but non-threatening presence, articulate but not severe. One by one, he uncovers the lies and manipulations this group has perpetrated on themselves or each other. Ultimately, we are left with the notion that there really was no Joe at all, just a bunch of townies stuck in their own psychological garbage and looking for someone to pin it on — in a larger context, think “regime” and “dictatorship” here. In the end, of course, no one can run away from themselves and the group is left limp with the truth — that they bear responsibility for their own situations as well as the collective situation of their stifled village.

Two time Obie Award-winner José Rivera is a wonderful writer, and many of the speeches in Massacre are thrillingly delivered. In 2004, he wrote the film The Motorcycle Diaries, artfully creating the young Che Guevara and his political awakening. Here, he is not as successful. The production is much too long and ultimately too wordy, leaving the viewer to disentangle long passages, taking interest away from the stage. The characters are a bit stereotypical — the hot town teacher, the homosexual, the black guy with a troubled sexual past — with the exception of Jolly Abraham and Adrian Martinez as the married couple, whose problems are perhaps more complicated and written as such. Oddly, the best acting is done by the most hypothetical character, Anatol Yusef as Joe. When he takes the stage, the whole tableau lights up with his clear, concise delivery as well as with his athletic presence and emotional nuance, which irrevocably drags the group of characters back to one another and creates a psychological realization. It is high camp and there is something satisfying in seeing the truth as uncovered by Joe — who, of course, has been lurking in the back of the characters’ minds all along.

But, in the end, it isn’t satisfying. We get that dictatorships are limiting and that people fool themselves every day in order to live with things they have done, but we crave something more; an awakening journey into the soul of the characters that hasn’t been parroted endlessly. Due to such a tangled mess, the question lurking on the spectator’s tongue is quite simply, ‘which play is this?’ If Mr. Rivera can find a way to shorten or disentangle his messages, we might get something newer and more interesting from them. Until then, we are left relentlessly trying to find our way through the overgrown maze of dialogue, getting lost in the middle without a way back or forward.

“Massacre (Sing to Your Children)” is playing at the Rattlestick Theater at 224 Waverly Place — off Seventh Avenue South, between Perry & West 11th Streets — in New York City through May 12. For show time and ticket information visit www.rattlestick.org.