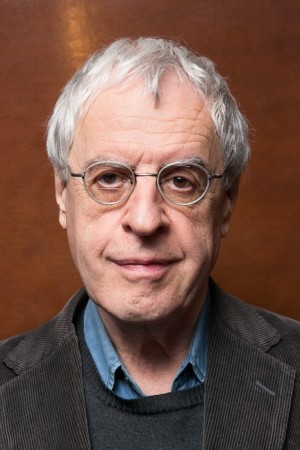

Charles Simic: A Man Who Does the Impossible

Charles Simic is undoubtedly one of the greatest poets in America today. Quite appropriately, three months ago, the man who had stated that “some people are more able to do the impossible” had participated in the PEN American Center’s World Voices Festival in New York City, in which he was translated among his peer poets from English into Spanish, garnering an even wider base. The honor of being considered one of the greatest American poets is amplified by the fact that Simic is an immigrant from Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia) and did not learn to speak English until he was 15-years-old. Since coming to the U.S., he has won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, has become co-poetry editor of the Paris Review, and has been appointed as a Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry. He’s published over 60 books, chief among them Walking the Black Cat, The Book of Gods and Devils, and The World Doesn’t End: Prose Poems.

Simic’s writing is as diverse as his experiences. War is a central theme in his works as his earliest childhood memories were of World War Two and his adulthood was forged by being drafted into the U.S. Army at age 23. Yet music, art, and city life are also all major themes for a man whose passions are jazz, painting, and films. Simic attributes these eclectic tastes to his father, who could always discuss tabloid gossip as well as he could sports, philosophy, or politics. Although the eclectic writer can be seen as a role model for making writing one’s craft — he wrote poetry at night as he worked as a salesman, housepainter, and payroll clerk among many other jobs — he does not like to consider himself a role model or any other kind of beacon of hope in this world. Instead, he is humble and modest about his success as well as his writing. Moreover, he is the first one to state simply that he just writes what he knows. Thankfully, despite his unpretentious ways, he graces us with his skill and will continue to write like only he can, while still teaching, translating, and making the world a better place, even if he refuses to admit it.

GALO: Were you surprised by which poems the students chose to translate for the event?

Charles Simic: Yes, I was. But this is typically the case. My work has been translated into, I don’t know, 30 languages? God knows. I lost count. Usually, what they choose to translate (the translators), is unknown to me. It’s not exactly the selection that I would have made. But that’s fine. That’s OK. There’s always an element of surprise. It wasn’t every poem in the case of New York University (NYU). But that’s what makes it interesting. They translate poems that I wouldn’t expect them to.

GALO: Translating is an act of choosing sides. One chooses to remain loyal either to the language or to the author. Did the students contact you with any questions about your works as they were translating?

CS: There was only one question, the poem called “St. Thomas Aquinas.” They didn’t know what a ghost ship was. There was a line [that said]: “I was on a ghost ship with sails fully raised.” They didn’t know what a ghost ship is, so I had to explain [it] and then they understood.

GALO: How did you explain it?

CS: I just spelled it out. It is a ship without a crew, found drifting in the ocean, in the sea.

GALO: Before beginning the readings, you joked that you don’t know anyone in the history of the world, who has made a living translating poetry, much to the visible cringing of one of your translators! Do you think translation can be seen as a career for young people to enter into today? Can it be an act of love and viability?

CS: It’s always a labor of love. It’s hard to find somebody who will publish translation. You have to be doing something else. You can’t make a living [out of it solely]. I never knew anyone who could make a living [out of it]. The only way you can make a living is if you are a famous translator and you translate books that are by authors with a world-class reputation. I’m talking about fiction writers and other kinds of writers, where the books are going to be distributed by major publishers. For poetry, nothing remotely like that can happen.

GALO: Do you think it should be like that?

CS: It’s not realistic to ever contemplate a situation where translations of poems are going to pay, where for the publisher it would be profitable. I’ve had a lot of friends in publishing over the years, but they would never publish one of my books in translation. I wouldn’t even bother to ask them. You lose money. There are not many people in this country who are interested in foreign literatures [laughs], especially poetry. Even fiction, foreign fiction, doesn’t sell. It would be incredible. But it’s not much better elsewhere. People in France are not buying translation of foreign poetry by thousands; in fact, they’re not buying at all. It’s a universal thing.

GALO: But in the instance of PEN, which is also true for their World Voices Festival, they’re trying to bring more international works into light, more translations into America.

CS: That’s always nice and it’s necessary to do this, but it has a fairly small effect. There was a time when comparative literature was taught much more in colleges and universities. Thirty years ago and before, most intellectuals, academics, readers in this country knew the names of the major fiction writers in Europe, South America, and some of those works were taught in school, in classes. That’s no longer the case. As far as poetry, foreign poetry, a little bit of it was known and continues to be known thanks to the writing programs, but not enough to make it for any publisher really profitable. Although, university presses continue to publish poetry in translation, but they get grants for this. There is a foundation in Santa Fe called the Levin Foundation and they give money to several small publishers for the specific purpose of publishing translation.

GALO: That’s very worthwhile! Would you maybe like to see a reversion in academia back to what it once was?

CS: Of course I would, but I don’t see that happening.

(Article continued on next page)