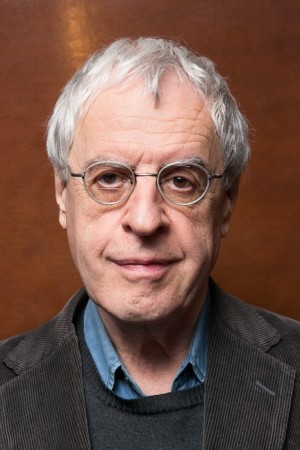

Charles Simic: A Man Who Does the Impossible

GALO: You had said at the event in May that when you read a specific kind of work, you say to yourself that you must translate it; do you feel translation is a calling of sorts? Does it take a specific kind of mind or heart or can any of us who are bilingual or trilingual do it?

CS: It requires a certain talent. First of all, you have to know something about literature. You have to know something about poetry. You have to know something about your language, the language your translation is in and the language that you’re translating from. Then what it requires is ingenuity. Some people are more able to do the impossible. Very often, poems are very difficult to translate, not because you don’t understand something in the poem, but because the poem is very concise or very craftily put together in the original language and that depends so much on the various aspects of that language — the sound, the associations, and if the poem is in traditional meter, the rhyme, the tightness of the stanza. To recreate that in another language requires talent, skill, and ability. Who makes a good translator? It’s hard to generalize.

GALO: But you would say writers are more apt to be translators?

CS: Yes. The people who translate poetry tend to be poets. I’ve known some people who are not poets, but who are interested in poetry. It is not typical. It is something one does not come across too often. It is usually a poet who translates poetry. It’s not like fiction; people who translate fictions are usually not novelists.

GALO: Was there any specific reason why you began the reading with the “Big War,” a poem about a child’s knowledge and understanding of the horrors of the world before his time through his interaction with a toy soldier, and then continued with a poem whose lines read: “We give death to a child when we give it a doll?”

CS: No, there was nothing very deliberate about these things. They were the order of the poems that I got from them. I knew it was going to be a very short reading. It was just the way the poems came to be.

GALO: What about when you were writing them?

CS: When I wrote them, God knows what I was thinking! I’m sure I was thinking a lot of different things! [Laughs]

GALO: [Laughs]

CS: The first poem, “The Big War,” I think that poem came [to an unfolding] when I was telling someone many years ago (I called that person Margaret in [the] poem, but it was somebody different) how it shook me, it struck me as absurd that during the Second World War, when I was a kid, bombs were falling on our heads and Germans were occupying us, and there was a civil war going on; we kids were playing war, we were playing with little toy soldiers [laughs], so the total absurdity of that!

GALO: [Laughs] On a smaller scale!

CS: I did have these clay toy soldiers, which was typical in Europe at that time. I had a bunch of them. I think I inherited them from someone, because there were no toys. You couldn’t buy toys during the war. There were no toy shops or anything. [Laughs]. I don’t know where I got those damn things. There was nothing in their heads when you broke them. When you are a kid, five, six-years-old, trying to find out what’s inside them. The bodies had a little metal wire to hold them up, it was clay, [they were] very beautiful things, but the heads were empty. Of course [laughs], by simply describing it like that, it became an anti-war poem. Empty-headed! [Laughs].

GALO: In “Paradise Motel,” you write, “in a mirror my face appeared to me/like a twice-canceled postage stamp.” Mirrors are a recurring focus for authors. Do you feel yourself affected by mirrors? Do you see in mirrors the idea of the image, another self, a lost identity, a reflection, a portal, or perhaps a trickster?

CS: Mirrors are interesting. I have a lot of mirrors in my poetry, for the simple reason that I find them interesting. I am not the only poet to find them interesting. I don’t know where to begin. It’s a huge vast subject, which can represent a lot of different things. But it’s that idea that an artist holds a mirror up to the world.

GALO: Do you think that through your role as a poet you hold a mirror up to society, in a kind of Shakespearean sense?

CS: No, those are big words. No, I never saw myself as some kind of role [model], something for society, to hold a mirror, to instruct, to enlighten, and so forth, because those would just be pretty words. Society has absolutely no interest in being instructed, enlightened, even by schoolteachers, not to mention poets and writers. It would be to me completely ridiculous to pretend that one is a shining light in humanity’s darkness — that the poet is the shining light, or any other way of describing the poet in this heroic role. No, nothing of the kind was ever in my mind.

GALO: Thank you for answering so honestly! A bit of an odd question, but I noticed one author had come up again and again throughout the entire week of the PEN Festival. That author was Herman Melville. Margaret Atwood and E.L. Doctorow sparred over the meaning of Moby Dick, Salman Rushdie mentioned it in his Freedom to Write Lecture, Tony Kushner and Brian Selznick all mentioned it in their conversations, and you referenced it in your reading of “St. Thomas Aquinas.” It seems that the PEN participants, writers of conscience, are all influenced by Melville. What is your relationship to him or to Moby Dick?

CS: Melville is a great writer. I like many of his short stories. Bartelby is one of my favorite short stories, one of my favorite stories, period. There is great writing in Moby Dick. The beginning of Moby Dick, the first 50 to 60 pages are just incredibly written. But the book is long. It digresses into descriptions about the whaling industry and so forth. I can’t say it is a novel I ever read again. I read the beginning of the novel several times because I love the beginning of [it]. Melville is a great writer, a major American writer, [but] I can’t say I have any kind of relationship toward him. It would be difficult to be influenced by a 19th century writer, especially if you are a poet.

GALO: Technology had been a major theme at this year’s PEN Festival as well. At the closing of the Festival, Rushdie admitted that he was cajoled into tweeting by a friend. Have you considered embracing Twitter?

CS: No. I don’t have the time. I’m busy enough. I have e-mail. I use the computer. There are too many of these distractions. You have to be obsessed. It seems a colossal waste of time.

(Article continued on next page)