Tbilisi at Night: When the Lights Go Down, A Silk Road City Comes Alive (Part 2)

Editor’s Note: This piece is a continuation of Benjamin Mack’s trip from Turkey to Georgia entitled “While Barnstorming Through Black Sea Turkey, Remembering the Tea and Biscuits (Part 1),” published on September 12, 2012.

Groggily, I opened my eyes. What immediately came into view were the thick curtains; understated yellow wallpaper; the wooden table beside the quilt-draped bed; the humid air with an artificially sweet tinge — I was at my grandma’s house, apparently. What the heck was I doing there?

Dimly, I tried to recall what I had been doing before I fell asleep. Walking over to the window, I suddenly remembered as I threw the curtain open. I wasn’t at my grandmother’s house: I was in Georgia. Not the state, but the former Soviet republic nestled deep in the oft-turbulent South Caucasus.

Getting to the nation of some 4.5 million along the western Silk Road had been nothing short of an odyssey: after landing in Anakara, I was forced to endure a 24-hour bus ride along the deep blue waters of the black sea before traversing the treacherous passes of one of the largest mountain ranges on Earth. Though the journey was more pleasurable than it sounds (for a full account, click here), it left me so exhausted that by the time my friend Tamar and her brother Misha picked me up at the main bus station in the capital of Tbilisi, my brain had already shut off all but the most essential of bodily functions.

Waking up, I quickly discovered the first thing about Georgia: its people are, hands down, the most hospitable on earth.

Almost immediately, we sat down for a meal. That’s when I learned the second important fact about Georgia: Georgians take their food seriously — very seriously.

Succulent beef, a salad of cucumbers and glistening tomatoes, bread as airy as a cloud, and cheese that was akin to mozzarella with a sour kick — after subsisting on nothing but tea and biscuits I’d smuggled from my home in Germany, it was a supra (Georgian for “feast”) for the ages. Washed down with crisp water much fresher than what guidebooks would have one believe (some advise boiling water before drinking it, though I thought it tasted fine straight from the tap, with no side effects) and a traditional wine from Georgia’s legendary Kakheti region (which can stand toe-to-toe with Tuscany or Napa Valley any day) amidst the informal company of the entire family (Tamar, Misha, and their mother and father), I decided this was not Georgia at all: this was Heaven.

As the sun sank lower in the sky — bathing everything in a brilliant shade of pinkish-orange — we chatted casually over the meal. I shared the tale of how I had arrived (a legend which already had seemed to take on a life of its own), and heard of the changes that had taken place after current president Mikheil Saakashvili came to power following the 2003 Rose Revolution. Moments like this are why I love to travel: the intimate family atmosphere, immersing myself in a nation’s culture in a way no tour company or hotel can provide, and a moment no postcard can recreate. It was, I decided, a fine finale to my inaugural evening in a country that was first united in the ninth century.

But we were just getting started. Tamar and Misha were determined to show me around town, so we departed the sprawling Soviet-era apartment complex and hopped on a marshrutka, or minibus, to head straight to the heart of the Old Town. Spectacularly frenetic and stylishly gritty, Tbilisi was virtually untouched by the 2008 war with Russia, and it’s easy to see why. Built along the steep banks of the Kura River (also known as the Mtkvari), the city is surrounded by jagged mountains, and has narrow cobblestone streets barely wide enough for a smart car to squeeze through, much less a tank.

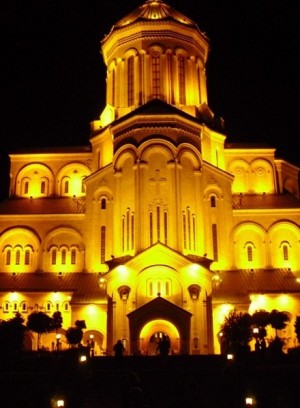

We quickly found ourselves at the Holy Trinity Cathedral, also known as Sameba. The third-tallest Orthodox Church in the world, the domed structure boasting no less than nine chapels has been lauded as an architectural marvel by some, and an eyesore by just as many. Regardless of the divided public opinion, its importance to the Georgian Orthodox Church is undisputed: the cathedral with strong Byzantine undertones is led by the Catholicos-Patriarch of all Georgia Ilia II (himself a divisive figure, offering in late 2007 to personally baptize any child born to a family that already had at least two in an effort to combat Georgia’s declining birth rate), who has a home on the grounds of the sprawling complex.

While wandering about, inside the cavernous main hall (and thinking how grateful I am to be a male, as women inside Georgian Orthodox churches are required to cover their hair), and admiring the virtually priceless paintings and other iconography devoted to various saints and other important figures from Georgia’s two thousand years of history (such as Queen Tamar and David the Builder), I was struck by how old a new building can be made to look: though only opened in 2004, if I had come across the cathedral during the 14th century, I would not have batted an eyelash. While tourists were in the majority, black-robed monks flitted amongst shadows framed by stone mosaics. Nary a mobile phone in sight, their presence stirred the imagination, conjuring images of medieval derring-do featuring fire-breathing dragons, duels to the death, and damsels in distress.

The rest of the evening was a blur: a peep at the presidential palace (coupled by a few curious moments amidst dozens of policemen and security as the president’s motorcade passed by), an aerial tram ride up to Narikala, a fourth-century fortress with spectacular views of the city below, and a bite to eat at what ranks as one of the most romantic cafes I’ve ever been too. The wraparound second-floor balcony — which strangely reminded me of New Orleans — set amidst a low brick ceiling and nestled against the side of a practically sheer cliff was decidedly low-key, despite the plentiful Saturday night crowd. The balcony full, we opted for a table nestled in a corner near a large open window that allowed the warm night air to waft in. A steaming plate of khinkali was brought before us, and here the adventure truly began.

Every country has national dishes, but few boast as distinctive a cuisine as Georgia. Although visited in times past by empires as varied as the Persians and Mongols and enduring over 70 years of Soviet domination, the mountainous topography of the Caucasus has for the most part kept ingredients and recipes local. Add that malaria outbreaks around the Black Sea kept travelers away until well into the 20th century, and the result is a unique gastronomy that borrows little from other locales. Khinkali is one such example. A type of large dumpling filled with meat, khinkali is typically eaten without any utensils by first sucking the juices out, in order to prevent it from bursting. The top where the pleats meet is not supposed to be consumed, but left on the plate so that those eating can count how many they have had. As it has been well-documented that there is a black hole where my stomach should be, I downed three of them.

Stomachs — and eyes — adequately satiated, we hopped on another marshrutka, barreling down the zigzagging streets pulsating with the teeming masses of humanity seemingly unconcerned with their nation’s recent struggles. The ongoing disputes over the status of the breakaway regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, the continuing disagreements with Russia, and the October 1 parliamentary elections that Western observers will have a keen eye on — none of that mattered. This night was for relaxation, for excitement, for joy under the bright mtvare (“moon”). This was the charm of Tbilisi, and I was enchanted.