The Essence of Contemporary Today

Women in Graffiti

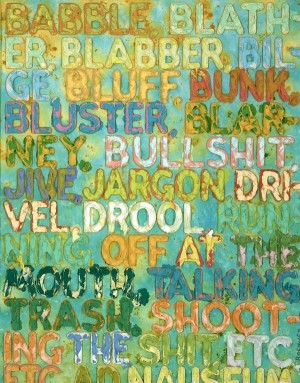

Graffiti art possesses an inherent shock value in that it often appears in places it’s not supposed to, frequently defacing public property.

Now it’s making its way onto canvases people pay hundreds of dollars for to hang in their living rooms — a new form of mainstream fine art, as is evident by artist Kirby Kendrick taking up her own set of spray cans.

“People are very surprised when they come around and wonder who the artist is and they see me,” she says, laughing, “because I’m a grandmother.”

But she isn’t running around tagging buildings at night.

“I wanted to show that the freedom and the spontaneity of graffiti and street art can become fine art,” Kendrick says, “Being referenced to as I said art history or referenced to something else other than just tagging.”

Photo courtesy of Kirby Kendrick.

Two of Kendrick’s major works on display, Olive and Dick Tracy, pay homage to major American cultural icons. Olive Oyl, the Madonna, and Lady Liberty occupy one canvas, opposite crime fighting comic hero Dick Tracy, Muhammad Ali, and radio show private eye Guy Noir.

It might strike you as a division claiming that girls can’t run with boys, but if anything, these softer more feminine figures not normally found prowling down dark alleyways, are holding down their own side of the block, grabbing some street cred with their harsh edges and neon colors. And simultaneously, they help to soften up graffiti art a bit, somehow helping it fit in as a home aesthetic.

But according to Kendrick, separating the boys and girls was totally accidental.

Art may exist for art’s sake. But if you consider the greater chain of being, art comes from people, and people are configured by the cultural, socioeconomic, and political forces in their environment.

Therefore, works of art represent varying manifestations of the world in which we live. They function in defamiliarizing us with our surroundings.

Leaving the art show, the world is made a bit stranger. Just like we might reflect upon human behavior and socialization in 1960 with the perspective afforded by hindsight, a removal from immediate context that highlights the significant potential for social change that existed — the question arises: How much farther can we go in 30 or 40 years? What will be contemporary then?

In the art world, it is perhaps something quite difficult to fathom in the present day. After all, “contemporary” is unusual and shocking in its essence, its aim to challenge existing conventions.

By highlighting the loaded nuances in the most mundane — words and objects that construct our everyday existence — we take heed of that which is taken for granted and the options we seem limited to, such as the attitudes and beliefs inherent in socially constructed gender roles.

Second-guessing the automatic throws a wrench in the rigid routine and the ruthless quest for self-improvement and for forward advancement — a pause for what it means to be human.

We open up our eyes and see the world in all its color and form, obliterating that black hole that we often fall into, where light from the outside casts moving shadows on the wall.