“War Horse” Is a River Current of Emotions

Viewer, be warned: War Horse will stir emotions like few films before. Tears will flow frequently and in copious amounts. It is recommended to bring a box of tissues (or two).

As the name might suggest, War Horse is about both a war and a horse. Based on the Michael Morpurgo novel of the same name, it is a mixture of some of the most appealing vistas ever shown on film, and some of the most repulsive — grand, sweeping panoramas of the English countryside bathed in golden sunlight predominate the first 30 minutes or so, giving way to dark, hellish images of World War I trench warfare that leaves ample amounts of dirt under the fingernails.

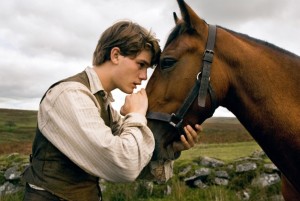

The pastoral vistas of the film’s early going closely follow the straightforward plot: Joey, a headstrong half-thoroughbred, is purchased at an auction in the rural English village of Devon by Ted Narracott (Peter Mullan), a stereotypically hard-working farmer with a drinking problem. The Narracott family also includes the short-tempered, yet loving wife Rosie (Emily Watson) and their son Albert (Jeremy Irvine), a strapping young lad, seemingly devoid of the typical teenage angst portrayed in so many films, who forms an immediate bond with Joey. In one particularly moving sequence, Albert teaches Joey how to pull a plow by first wearing the harness himself, and together they ride through the stunning scenery that makes England so famous.

A cantankerous goose also calls the Narracott farm home, and he’s nothing if not a hoot; a particularly humorous sequence involving the goose menacing a group, including the Narracott’s landlord (David Thewlis), ranks amongst the film’s most tender. Director Steven Spielberg seems to have lifted the character directly from the talking duck in Babe, although in this case, the waterfowl remains (relatively) silent.

Yet despite all the tenderness and charm, a certain kind of darkness permeates throughout the film. Ted is haunted by memories of fighting in the Boer Wars in South Africa – an experience so haunting, he cannot even speak to his son about it – and struggles to support his family. The specter of the impending outbreak of World War I also casts a further gloom over the pristine pastureland, stoking a nationalist fire within the souls of the residents of Devon.

The senselessness of war is shown through the titular horse’s eyes. After being sold by Ted (to the utter shock of Albert, in a powerful scene that gets the waterworks going early), a series of owners – from an English major and a German soldier to a French girl and another German soldier – meet decidedly dismal fates. While the unspeakably extreme violence of World War I is implied far more than graphically depicted (a welcome departure from Saving Private Ryan that moviegoers, and their stomachs, will undoubtedly appreciate), the emotional impact is no less profound. As Joey bounces between owners, a connection is built, only to be smashed by the relentless march of war.

But just as poignant as the human casualties is the loss of a way of life. Joey begins the war as the prized mount of an English major, but four years later (in 1918) he is used by the Germans as a pack animal to carry titanic machine guns up a hill, with little regard for his condition, or even his life. The time of horses as essential to everyday life, the film says, has passed.

Joey is not the only character whose innocence is lost. Albert later joins the war as well, and the price he pays is steep: not only is his best friend killed in trench warfare, but he himself is almost permanently blinded by gas; by what he experiences, the war literally represents a coming of age for Albert, not unlike the works of such poets as Thomas Hardy.

Albert, also makes his own way to the war, and his and Joey’s parallel experiences – harrowing escapes, the loss of friends, and the terror of battle tempered by the hope for a brighter future – add both texture and momentum to the overall narrative (not to mention provide Spielberg with an opportunity to show off his favorite editing method). At the same time, the supporting cast – almost entirely British and virtually all male – performs with a sublime understatement that never appears forced or artificial.

Irvine’s performance as Albert, though admittedly corny at first, is believable enough. He straddles the lead/supporting actor line with a confident brilliance, never upstaging the horses that portray Joey in the numerous scenes they share. The rest of the cast is also keenly aware of their background roles – after all, much of the war is shown through Joey’s eyes. Taken as a whole, the cast ranks among the strongest Spielberg has worked with, making the most out of their limited screen time.

Perhaps just as outstanding as the performances is Spielberg’s lack of CGI usage. While he could easily have utilized technology liberally – particularly during a sequence in which Joey comes face-to-face with an armored tank bent on running him over – every shot remains unaltered, as much a testament to Spielberg’s vision as the extensive training the horses that portrayed Joey underwent.

Sure, there’s a strong antiwar message shown through the transformative power of military conflict, but at its heart War Horse is a story about the relationship between a boy and his horse. Predictably the two are reunited for a presumed “happily ever after” ending. That does not make the reunion any less emotional, however, when Albert meets Joey again after the latter is rescued from the dreaded “no man’s land” (the hellish area between opposing trenches riddled with land mines, barbed wire, and various other booby traps), tears will flow from viewers as much as Albert. Indeed, the scene ranks among the most emotional depicted on screen in recent memory, and is easily Spielberg’s most moving since E.T.

The emotional current of War Horse is a powerful one, the tide of which may thrust the film into the 2012 Oscar discussion. But regardless, the pull of the film at the heartstrings is one of a commonality most share — the love of one another and the love for the species equus ferus.

Rating: 4 out of 4