Tribeca Interviews: ‘Obit’ Shows Doing Justice to a Life in 800 Words Is Harder Than It Looks

Director Vanessa Gould. Photo Credit: Joseph Moran.

Éric Joisel spent the majority of his day looking at paper. As an internationally renowned origami master, he could transform unimaginative, bland sheets into a miniature band of musicians, an African mask, even Gandalf from Lord of the Rings. Sometimes crafting it would take hours, other times the piece demanded years of his attention. He attended to these paper forms so carefully, but who would remember his death?

That’s the question director Vanessa Gould asked herself two days after Joisel died of lung cancer in 2010. She had worked with Joisel through her Peabody award-winning documentary Between the Folds (2008), tracing the careers of paper artists and scientists. After becoming friends, Gould was anxious that his life would not be remembered. This worry of impermanence inspired the film Obit, which had its world premiere at the 2016 Tribeca Film Festival.

“He was utterly unique; a lot of people in the art world work in collaboration, and this man was sort of working on his own, doing things that other people didn’t really know how to do,” Gould says. “So when he passed away, I had this sort of panic about what would happen to his legacy and if his memory would evaporate over time.”

Gould reached out to several newspapers to tell them about Joisel’s effusive and eccentric life. Unexpectedly, only one responded; perhaps even more surprising, it was The New York Times. After working with reporter Margalit Fox to share his artistic achievement, Gould became interested in the NYT obituary department as a whole.

The five years of research, filming and production of Obit have taken the print medium of obituaries and made it visually appealing. While death is often depressing and devastating, an obituary can become closure, comfort, even an honor. This film shows that the difficulty of writing an obituary lies within the reporter trying to grasp the purest essence of one’s life, rather than simply transcribing a resume.

GALO spoke with Gould about her reaction to only one publication responding to Joisel’s passing, why humor is important to feature in a film about death, and what she thinks her eventual obituary will say.

GALO: Were you surprised that The New York Times was the only publication that responded to you?

Vanessa Gould: I was pretty shocked and pleased to hear from them. But as I was helping the writer research the piece, I just couldn’t really believe that this leading national newspaper would commit such precious real estate in their pages to somebody who they had never heard of before and who was working in such an obscure medium that none of their readers would have ever heard of them. That made me sort of ask questions of: “What is The New York Times doing here? Why are they committing some of their best journalists on the news desk to writing about people that didn’t necessarily have a familiar name with their readership?”

GALO: Did they ever tell you why they picked him?

VG: They did! In some ways, it would be a similar answer to the way that they pick a lot of their subjects I haven’t heard of. Generally, what I think the editors would say — and I’m doing my best to paraphrase them here — is that they’re interested in covering the story of somebody who truly changed the world or some portion of the world in a way that no one else has.

So whether it’s an artist working in an unusual medium who excels in their field or someone who wrote a book — even if it was within a certain subculture — through a series of ripples and currents, it sort of changed everything that followed. I think they want to commit those people to the public record. Maybe in a way more than someone who had achievement but it was singular.

GALO: After winning the Peabody Award for Between the Folds, what types of films were you inspired to create? Was Obit along the lines of that or was it a detour from what you were aiming for?

VG: I’m pretty much a documentarian through and through; I think that’s sort of in my blood. I had a really great experience with Between the Folds, and I think that when I won the Peabody, it was pretty reaffirming that was the direction I was going in — in terms of the medium I was working in. It sort of allowed me to keep my eyes and ears open for whatever might come along that interested me, since something about paper art and origami was well-received.

GALO: Is Obit your first film that’s appeared in the Tribeca Film Festival? And have you seen more female directors the longer you’ve been creating films?

VG: It is the first film of mine that’s been in the Tribeca Film Festival and we’re thrilled about it. I’ve probably seen more female directors; it’s nice to see the level of encouragement. There’s a ton of organizations that are committed to supporting female storytellers. Several of the nonprofit funding agencies like Impact Partners, Chicken & Egg and the Fledgling Fund are all very attentive to female filmmakers.

GALO: What techniques did you use to make the print medium of obituaries visually interesting?

VG: That was a big challenge; it was something we were thinking about from the get-go. The interesting conundrum is that obituaries work very effectively in print, it’s what they’re made for and that’s how they thrive, so to sort of shift that medium to one that’s both visual and timely took a fair amount of anxiety and thought for me. We put a ton of effort into representing the obituaries that were printed on the page pretty authentically without a lot of bells and whistles, so we were really going for a beautiful, flat, textured recreation of the obituaries that you see on the page. And we really strive to make that same format work on the screen. We even put effort into what obituary we want to show based on which obit had particularly compelling and riveting photos. We looked at a lot of pull quotes and headlines to study. With Michael Jackson, we really pushed on his headline because it said he was idolized and haunted, two adjectives that sort of get to the core of the complexity of his life.

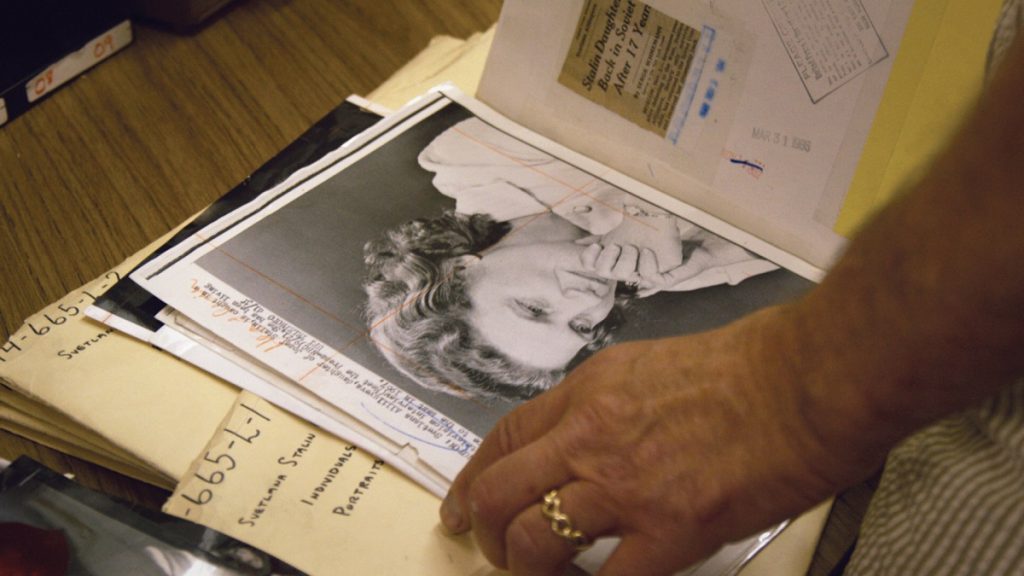

A glimpse into an old folder in the New York Times morgue. Photo Credit: Ben Wolf.

Last remaining archivist Jeff Roth searches the New York Times morgue. Photo Credit: Ben Wolf.

GALO: Was there anyone besides Michael Jackson that when you were looking at obituaries to include you said to yourself, “This one has to make it in?”

VG: Not really, as a filmmaker I wanted to see — within the process of interviewing — how the stories and the film were going to be curated. I sort of let the ones in the film come to me, since those are the ones that the writers remembered writing the most, which is a pretty telling thing given the steep learning curve that they learn on a daily basis and the amount of information they have to shed so they’re ready to write another one the next day. It’s sad to say but they rarely remember much, it’s an occupational hazard.

Many will tell you that by the time that they get home at the end of the day, they can barely remember what they wrote about. They go in such a focused state. So when I was interviewing them and they remembered someone really well, I would know [that] this is something that I need to pay attention to.

GALO: There were distinctive pockets of humor in the film, especially in Jeff Roth’s domain of the “morgue” — the NYT archives office. How did you decide when it was appropriate and necessary to insert humor in the scenes?

VG: That’s a good question. I haven’t actually been asked that much about the humor. In some ways, this film is about death, but in other ways, this film is about life. Humans often invoke humor as a way of managing their emotions. These obituary writers learn to see humorous angles as a way of offsetting what might otherwise be a melancholy thing to do every day. So when I was speaking to [the reporters] in the interviews, I was constantly looking for the humor — and it came, it’s with all of them. They’re all really intelligent and funny people, they sort of found their own ways of looking at death with humor. I wanted to make sure that the film reflected that more than the way I would ever see humor in it as an outsider.

GALO: After shadowing the NYT’s obituary writers, what do you think is the hardest part about writing an obituary?

VG: To me, everything seems really hard. The more I learned, the more I was slack-jawed at the skill and the experience that they all bring to it. I think for every person it’s different — for me, the deadlines and the fear of errors would be paralyzing, but someone else might say the difficulty is the information they have to learn and how to contextualize a life so quickly into the greater picture. On any given day, you’ll get a different answer.

GALO: NYT writer Margalit Fox said something interesting about the paper receiving criticism for not publishing enough obituaries of women or minorities, although there have been more obits published for these groups as time goes on. What did you think about when she said that?

VG: My goal with the film was never to turn the camera on and observe the issues of demographics of the NYT, which reflect the demographics of the culture. We could have pushed them further on this idea, but they’re doing what they decided to do institutionally and I wanted to play a more passive role as a filmmaker. I think if audiences watch the film and have their own thoughts about the issues of gender in contemporary society, and how they’ve evolved over the past century, then that’s a fantastic thing.

I never wanted to either defend the NYT’s position or challenge it, but leave it stated as it is by a representative of the paper, and let the people who watch the film form their own judgments about it. You’ll see that [in the NYT‘s obituary history] there’s a preponderance of men the more you go back in time. If I had started to take issue with that as a filmmaker, it would have become more of an opinion piece, and that wasn’t something I thought I could do in 90 minutes.

GALO: Do you think differently about death after directing this film?

VG: Probably. It’s funny; the writers will say the same thing — that you can’t really let yourself dwell on the Meta levels too much. It’s really counterproductive. In a more indirect way, and this is the reason why some people are drawn to obits, the mere fact of reading about so many lives and people that took bold steps in their lives and made decisions that were unusual awakens us in some way. It makes us appreciate our lives better, and maybe the specter of death can motivate in certain ways.

GALO: I know this is a slightly morbid question, but what do you hope your eventual obituary will say?

VG: [Laughs] Oh, I don’t think I’ve ever thought about that. It’s really funny, as a filmmaker you get so focused on your subjects and the perception that the audience will have. Me as an entity has been very peripheral in my life for the past five years while I’ve been making this film. I can tell you quite truthfully that I have not thought [about] my own obituary as much as the others.

“Obit” made its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 17, 2016.