Matt Shepard: A Friend to Us All

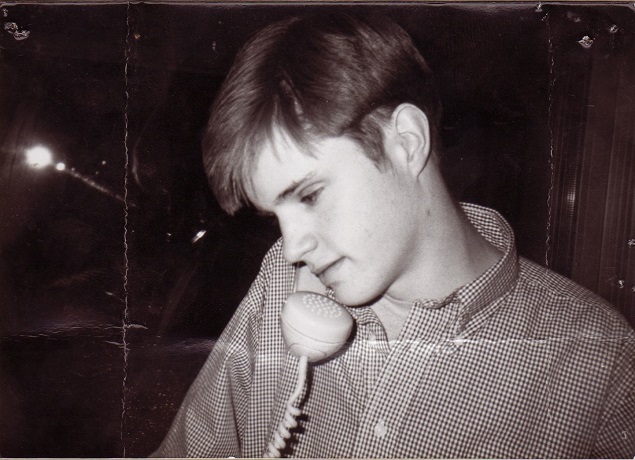

A still from “Matt Shepard is a Friend of Mine.” Photo courtesy of: Run Rabbit Run Media/The Shepard Family.

Some lives are like Edna St. Vincent Millay’s famous poem, First Fig:

“My candle burns at both ends

It will not last the night

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends–

It gives a lovely light.”

Matthew Shepard had so much to live for. But on October 7, 1998, barely two months shy of his 22nd birthday, he was brutally beaten, tied to a fence, and left to die. It’s a terrible tale to tell — one more gay man destroyed by a hate crime almost beyond imagining — but Michele Josue’s film, Matt Shepard is a Friend of Mine, does his story a beautiful justice. Through the testimonies of so many lives he touched, we are given the opportunity to witness the brief shining burst of flame that was Matt Shepard before it was extinguished forever.

For those readers perhaps too young to remember the event, two Laramie, Wyoming residents — Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson — both in their early 20s, met Shepard in a local bar over beers, pretended to be gay, and corralled the lonely, unsuspecting man into leaving with them. The subsequent attack, which resulted in Shepard’s death soon afterward, ignited the ire of an entire nation, further polarizing the strict fundamentalist community from gay and liberal sympathizers across the country. Journalists from here and abroad descended upon the small town, and Shepard became the poster boy for a whole generation of LGBT citizens.

It’s a formidable task that director Josue, one of Shepard’s closest childhood friends, set for herself. By lovingly threading together rare video footage of Shepard with family, friends, teachers and associates — even the Laramie, Wyoming bartender who remembered him that fateful night — we get a remarkably focused picture of his personality. Interweaving shots of the Wyoming landscape at different times of the day and night, we are introduced to the lonely expansiveness of the place he called home — 100,000 square miles we are told, home to barely a half million people — a place with a live and let live philosophy, “as long as you live a little farther over there, please.”

If the physical landscape was arid — and lonelier on a human scale than the mind could encompass — the day to day reality for the boy was anything but unpopulated. According to one of his teachers, “he was the guy that could be in any group — he looked into your eyes — what a spitfire!” He was dubbed “a pocket gay” by one of his teenage friends, weighing in at 110 pounds with a height of 5 feet 2 inches. He might have been small but he had giant dreams. We see close-ups from his notebooks, describing him in his own sloppy, in-between the lines handwriting as “hardworking, honest, sincere…sometimes messy and lazy…I am my own person…I love airports.” He wanted to see the world and he did, at least a lot more than the local kids in his high school drama club probably ever would.

Of course that changing scenario in his life created an exhaustive search for our filmmaker. His father, Dennis, who was employed in the oil industry as a safety engineer, would be transferred to Saudi Arabia with wife Judy, along with Shepard himself and his younger brother. That was quite a sea change, even for the 10th grader. As there were no high school facilities where his father was stationed, Shepard was sent to a prestigious school in Switzerland. Tracking down the friends and acquaintances during this phase can’t have been an easy one for Josue, as well as eliciting the heartfelt confessions of those who loved him. It is her debut film and the first one made by an intimate of his circle. One surprising episode recounted by a fellow student involves a study trip to Marrakesh, Morocco, the first trip of its kind for the school outside the geographical confines of Europe and considered a risky enterprise at the time. Unfortunately for Shepard, curious about his new environs, risk became reality when he was robbed and raped by a band of local thugs.

Judy noticed the change in her son after that traumatic experience, his hunched shoulders and shuffle in the walk. His decision to return to the States led to a short interlude in Denver, where he made some effort to be part of the active gay community there and finally confessed the truth to his mother. She admitted knowing all along and told her son, “It’s a mom thing.” Lonely in Denver, he made the decision to move back to Laramie and attend the University of Wyoming, where, according to his beloved guidance counselor, Shepard felt safe. We sense from that same counselor the paradox of encouraging the young man to feel comfortable with the familiar, when in fact he found himself in a place where being branded an outsider can be the most dangerous of all.

The real strength of the documentary lies in the down to earth honesty and vulnerability of Josue’s participants (the filmmaker herself being an eloquent one), particularly Judy, who knew for her own survival that it was up to her to start The Matthew Shepard Foundation immediately following his death, combating the continual onslaught of hate crimes across the country against the LGBT community. It is in no small part due to Shepard’s parents’ final acts of forgiveness during the murder trials that both attackers received two consecutive life sentences rather than the death penalty. And it is the Foundation’s ongoing work toward greater understanding that she feels Shepard would have been immersed in had he lived.

To the filmmaker’s credit, she has provided enough intermittent cuts of happier times — Shepard being playful with his younger brother, smiling openly with his braces, posing for his father on a family junket to Rome, hanging out with girlfriends who so unabashedly enjoyed his company — that we can appreciate his life as it was lived. The music, composed by Nicholas Jacobson-Larson, is never intrusive but fits the multilayered moods of this ever-changing collage of a life. The video coverage, especially in his younger years, is a little roughly executed, occasionally out of focus, but like a patchwork quilt resulting in a picture much richer than its individual scraps of footage.

Of course, the inescapable recounting of the crime itself and its aftermath — the comatose victim in his hospital bed, the angry reactionaries carrying hate signs outside St. Mark’s Episcopal Church at the funeral, ie. AIDS cures fags, the two attackers seen in brief courtroom footage — are all essential for a complete understanding of how this crime affected the country at large. Comprehensive footage includes celebrities like Bill Clinton asking us to search our hearts, an enraged Ellen DeGeneres speaking at one of the many rallies, and later, President Obama signing into law in October of 2009 much needed hate crimes legislation.

Cleveland’s Plain Dealer said of the documentary’s impact, “No film is more poignant or relevant to the history of LGBT folks in America.” The film has deservedly won four Best Documentary awards and will be released in select markets across the U.S. and Canada in February of this year. That is an impressive record for this young and intrepid director. Her almost overwhelming research, in order to leave us with as honest of an account of her friend’s life as she could produce, is evident.

Maybe the greatest danger in such a tribute to her subject is elevating him in his death to a kind of sainthood. The viewer doesn’t doubt that he was a sensitive, caring young man to his family and friends, but his search for an identity he could live with was a troubled one at best. A more balanced approach in characterizing the young man would have given the film ultimately more depth without tarnishing the tragedy of his loss.

The tearful testimonials can be almost unbearable at times to watch, as they exhibit the kind of personal pain that can’t be easily eradicated, nor should it. Perhaps it’s through such tragedies that we can face our common humanity and the dignity and acceptance we owe to others. There’s a responsibility in viewing such stories not only to never forget the multitudes that perished in events such as the Holocaust or our recent 9/11 tragedy, which are obvious choices, but the preciousness of a single life such as Matt Shepard’s — a friend to us all.

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars

Video courtesy of MyFriendMattFilm.

“Matt Shepard is a Friend of Mine” is currently screening at select locations nationwide. For a schedule of upcoming screenings, please click here.