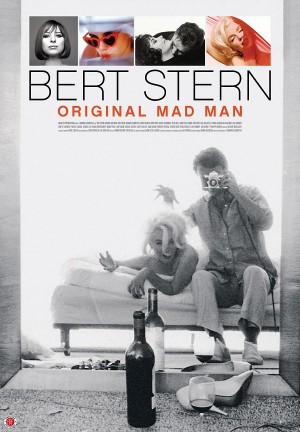

Lover or Madman: The World of Bert Stern

Was Bert Stern a lover of women? Yes. Was he a seducer? Yes. And was he a madman? If you take Shannah Laumeister’s appellation for him in her new documentary, Bert Stern, Original Mad Man as a double-entendre, perhaps it’s true. But in today’s fractured world that’s a heady claim to make. What he became — and this is a pretty fair assertion by almost anyone’s standards — was one of the 20th century’s greatest photographers. He revolutionized Madison Avenue with his images and turned celebrity photography, along with Richard Avedon, into a lasting art. If he had a roving eye in more ways than one, so be it. He had the eye.

If this was a documentary strictly about Stern’s images, it would be more than enough. Seeing the hypnotically-charged young photographer creating a campaign for Smirnoff Vodka, “the driest of the dry,” convincing his employer to send him to Egypt to capture the Great Pyramid as seen inverted through a martini glass, you see the touch of genius at work. His talent at conceptualization would catapult him to the apex of the advertising world. Smirnoff’s was a hugely successful campaign. And brief accolades from ad world wizards like George Lois and Jerry Della Femina are quick to attest to his particular uniqueness in their realm. According to Femina, “this was not a country that drank vodka.” One of the little ironies of the campaign was the condition that women not appear in ads featuring alcoholic beverages. Because of that restriction, womanizer Stern was able to prove once and for all that he could shine even when his beautiful female props were absent.

But what was it about women that fascinated him most? In his work (and that’s where they fared best) he glorified, idolized and in some instances, immortalized them. In his words: “I’ve always loved women. I think being a woman must be very difficult. After all, you’re always on the inside. Men look at the outside. It’s that illusion which is so delicious.”

No woman personified that ideal more in his art than Marilyn Monroe. What he managed to do in two sessions — one largely shot nude except for a series of transparent scarves — became the stuff that legends are made of. Tragically, when Vogue finally published the iconic images, they appeared on Monday, August 6, 1962, one day after her terrible demise.

There’s a bittersweet regret in the elderly Stern’s recollection. He saw himself as “just a kid who wanted to photograph Marilyn Monroe,” with no idea of the depths of what she was going through at the time. Though Monroe was a willing collaborator during their intimate sessions — the stylists were kept at bay behind locked doors — he frankly admits that it wasn’t a conquest. The actress was in high spirits on champagne spiked with 100 percent vodka, but the photographer had taken half a Dexedrine which evidently enhanced his creative energies but not his sexual drive. Even when she sent back the proof sheets, many of which were scrawled out with an orange magic marker, he celebrated these images, finding the orange “x” marks over the black and white contours of her body downright “delicious.” Luckily for the viewer, Ms. Laumeister isn’t a bit stingy with the stills that emerged from these sessions, understanding that the woman was one of Stern’s chief obsessions.

Another overriding obsession in Stern’s personal life was the prima ballerina Allegra Kent. At the time he first encountered her, she was George Balanchin’s favorite, but Stern was convinced she would make a beautiful mother. The archival stills and videos of their time together show an impassioned couple with their three children, living high, too high not to come tumbling down. From the interviews with Kent, it would appear that it was Stern who fell the hardest, suffering a breakdown severe enough to end the marriage. When one doctor puts him through a new age controversial therapy, causing him to see a whirlwind of images from his life, film director Laumeister gives us a kind of Luis Buñuel-esque montage of his experience.

Whenever the film director breaks away from Stern’s own morose, often regret-filled account of past experiences, it is a welcome change. Time has not been particularly kind to this man who had a handsomely intense attractiveness to the opposite sex in his younger days. The filmmaker was in awe of him as a young teenager and his camera loved her nubile freshness. Her 20-year history with Stern, as a mentor and largely soul mate in his later years, feels at times highly subjective. What the camera’s eye shows when the tables are turned on Stern himself is somewhat different. He inhabits a world-weary, deeply-lined face, a man who can be in some moments highly revealing about himself, sometimes blisteringly so. In other moments, pacing around his Sag Harbor home in a white terrycloth robe, or reclining in his bed, we see the bored lassitude of a modern day Caesar, accustomed to women waiting on him.

There’s a richness of film research in Stern’s early life — from the imagined drug store where he worked at 13 as a soda jerk; to the hustle and bustle of Manhattan in the ’50s; to a depression baby from Brooklyn, working in Look Magazine’s mailroom could smack of the glamour to come. His nostalgia describing these early times with the magazine’s photographer, Stanley Kubrick seem the happiest. Fame and its relentless pace was just a heartbeat away. After a brief photography stint during the Korean War, he would soon be widely recognized and well-compensated.

Another interlude that gives the film a pleasurable jolt is Stern’s filming of Jazz on a Summer’s Day. This creation is a wonderful tribute to a jazz festival in full swing, with spectators and performers alike reveling in the pure sounds of the moment. Rare footage of jazz legend Anita O’Day scatting away at the mike in a black dress with a wide brimmed matching hat is perfect. As critic Judith Crist recounts of the film, “There’s not a moment that wouldn’t be a stunning still picture.”

All in all, Laumeister has assembled a talented crew for this documentary profile. The editorial team of Danny Bresnik and Piri Miller, the music composition by Starr Parodi and Jeff Eden Fair, and the special effects by Pic, Jarik Van Sluijs and Pamela Green are of particular note.

Finally, the stills are what we take away from this documentary. Their rapid-fire inclusion, from Buster Keaton and Marcel Duchamp, Marlon Brando to Burton and Taylor from their Cleopatra lovemaking days, Lee Radziwill to Lily Tomlin’s infectious grin, Sophia Loren to the irrepressible Twiggy — they’re all here. And they’re infused in the second of the shutter’s click with the magic that only a great photographer can give them.

That’s Stern’s final gift to his public. As for the gift to himself, only the artist can answer that.

Rating: 3.5 out of 4 stars.

(“Bert Stern, Original Mad Man” opens nationwide from April through June, 2013. New York City dates are scheduled for Symphony Space starting May 26, 2013. For a full schedule and ticket information, please visit http://firstrunfeatures.com/.)

Featured image: “Bert Stern, Original Mad Man,” directed by Shannah Laumeister and released by First Run Features. Photo Courtesy of: First Run Features.