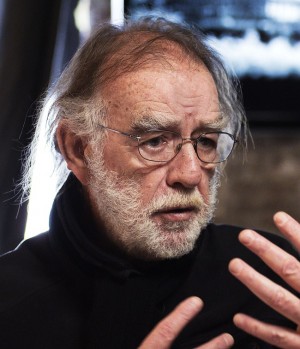

Godfrey Reggio, the Shakespeare of Poetic Cinema

GALO: It sounds like a pretty meditative process that you have when you’re coming up with the talking paper and the ideas that go into it.

GR: I do that all by myself, and with a colleague in Santa Fe. Once I have that somewhat in focus or I can feel it more than anything, I can feel it and speak about it, and if I can speak about it, we can figure out how to shoot it. At that point, I start sharing it with my colleagues.

GALO: Do you think that kind of approach to your films comes from your background as a monk?

GR: You know, I can’t answer that. I think there are other analogs. Art usually proceeds that way. You might have the subject in mind but the canvas speaks to the artist. It tells her what to do frequently. Certainly, let’s take sculpture — you might find a statue you want to make but until you become intimate with the stone, knowing its grooves and knowing where its faults may or not be, you won’t be able to sculpt it, and then the stone tells you how you can cut it literally. So it’s similar to that but rather than the norm of cinema — theatrical screenplay, knowing a priori actors or stars — it’s a wholly different process of putting it together.

GALO: Your films lie outside of what most people would consider to be mainstream Hollywood cinema.

GR: I think that’s an understatement, yes [laughs].

GALO: You’ve said that you’re not interested in making those kinds of movies. What about more traditional cinema deters you from that filmmaking style?

GR: It’s not that I’m critical of traditional cinema. I’m in admiration. I’m not a big devotee because we kind of become what we grew up with. I lived in a religious monastery for 14 years as a young person, from 14 to 28 [I lived] in the Middle Ages, so movies were off the radar completely. My life was changed by a great movie master, Luis Buñuel, and his [style] is more in the traditional cinema but in the modality of surreal. I wasn’t entertained at all by his film; I had a religious or spiritual experience — that film was called Los Olvidados (The Young and the Damned, 1950). I saw it in the early ’60s and it changed my life. So, the power of cinema is palpable. I don’t make the other films because I don’t feel them, and it’s not something I’m moved toward. I’m not interested in a career in cinema. I want to do everything I can to find the films that are within me and this is the form that I take.

GALO: Why did you decide to shoot in black and white?

GR: For a number of reasons. One, color contemporizes the image. Two, precognitive experience — when you see color, your eye is drawn to the different hues of the color. It’s how we put it all together into one. So there’s an element of distraction there. And three, and most importantly, I think black and white is more emotive because it doesn’t deal with representation. It deals more with form. I felt in this film that black and white would be perfect. Beginning the film, of course, is the moon, and the moon has no atmosphere, so I wanted to follow that through. I thought it would watermark the audience in a more efficacious and powerful way. And because it’s poetry, it doesn’t have to deal with being contemporary. This film isn’t to the intellect, it’s to the soul. It can take you on a journey you’re not prepared for. I always recommend leaving expectations at the door.

GALO: Can you describe the process of scouting locations for the shoot?

GR: If this film had been shot in 2005, the chaos in Louisiana from the hurricane would be obvious. However, five years down the road it doesn’t look like the chaos from a hurricane, it looks like the ruins of modernity, which is what I wanted the image to look like. To me, it was like having multi-bazillion-dollar sets available that couldn’t be produced in Hollywood. Also, I’m from Louisiana and the swamps, the trees, those are things I grew up with that I was intimately knowledgeable of and moved by as a kid. The big tree [a shot in Visitors] is one I played on as a child.

GALO: It was also shot in New York and New Jersey?

GR: Yes, it was shot in New York, mainly in studios in Brooklyn, and in New Jersey at this huge dump site there. [There’s a shot of a cascading garbage heap in the movie.]

GALO: This film was in 4K digital projection.

GR: It was shot in 5K, but produced at 4K. There are very few films that are seen in 4K right now. There are some 4K projectors, but not huge amounts. There are even less films being made in 4K. That’s going to start changing because the technology’s ubiquitous. But when I shot it, I had a prototype camera before it got on the market.

GALO: Why’d you decide to project at 4K?

GR: Again, it’s poetic cinema, so it’s about pictorial composition. For me, the more powerful, more present the images on the screen — which means the most resolution — the better it is. It’s not cerebral, it’s sensorial. I wanted the medium to be as experiential as possible.

GALO: Ultimately, what do you want audiences to take away from Visitors?

GR: The meaning is in the eye of the beholder. What is the meaning of the Mona Lisa? Well, everyone sees a different picture. That’s its meaning. It’s an auto-didactic form of filmmaking. The audience is at once the screenwriter, the storyteller, the character in the plot of the film. We all see different pictures. There are 50 people in the theater and after half of them leave because they can’t find the meat on the hamburger on the bun, the other 25 will have a vastly different experience. If you’re going into the film looking for the meaning of it, you’re going to miss everything that’s there. It’s all about seeing. Visitors come to see, and this is what the film can offer.

“Visitors” will open on January 24 at Sunshine Cinema in New York City, with a national rollout in select theaters to follow.

Video Courtesy of: Cinedigm.