Anders Petersen – The Passionate Photographer

Passion can have some strange beginnings. For Swedish photographer Anders Petersen, his relentless passion to capture life with a camera began in a strange way indeed. In Anders Petersen, recently published by Max Ström (www.maxstrom.se), and the largest monograph of his works to date, Petersen shares a telling revelation. Sometime in the mid-1960s, his eye was caught by a photograph of a Parisian cemetery. A freshly fallen snow revealed tracks of footprints in between the headstones. “It was as though the dead had risen from their graves during the night and strolled around, visiting each other,” he confessed.

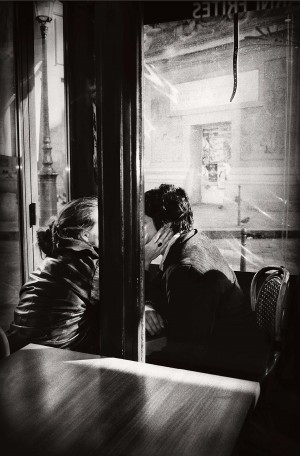

It was this experience that led Petersen on the road to becoming one of the most internationally renowned and respected photographers in the world today. The monograph, including more than 250 of his arrestingly intimate black and white images, is a cause for celebration for anyone who believes in the power of photography to move and sometimes even transform us from our everyday realities.

Petersen’s passion has taken him from a low-life bar in Hamburg, Germany to homes for the aged; from prisons to psychiatric clinics. His subjects cover the whole of humanity, and if the faces we see staring back at us are often not pretty, he makes us continue to look. He makes no apologies, for it’s the naked truth he’s after.

The Photographer

Born May 3, 1944 in Solna, Sweden, he had not yet found his vision (or vision had not yet found him) when his parents packed him off to Hamburg to learn German. He wasn’t the best student we are told, but he was a lover of people and made friends among other drifters and photographers. Returning to Stockholm, it was the encounter with a student at Christer Stromholm’s Fotoskolan that opened his eyes to his own future. For, as fortune would have it, the photographer of the aforementioned haunting image of that cemetery in the snow was none other than Stromholm.

Hasse Persson, a former curator at the Hasselblad Centre and Kulturhuset Stockholm, has written one of the two informative essays in the monograph about Petersen’s early exposure to the photograph in question and the artist’s quoted reaction. He goes on to describe how the young man, furtively using the school’s darkroom with no right to be there, came face to face with the man who would become his mentor for the next 30 years. After nervously showing Stromholm a box of his prints, the culprit was exonerated and admitted into classes. In that instant, a photographer of the people was born.

Perhaps the most seminal example of Petersen’s uncompromising style among over 20 books published to date is Café Lehmitz. For three years the artist haunted this Hamburg bar, making himself a regular habitué, but more importantly, a trustworthy observer and friend to the prostitutes, transvestites, drug addicts and the rest of that café’s motley clientele.

Urs Stahel, curator, art critic and director of the Museum for Photography Winterthur in Zurich, explains, in a second illuminating essay from the book, Petersen’s working method: “…he has cast aside superficial appearances, fearlessly grasping all manner of thorny issues. Petersen is ‘hypnotically intimate.’” This quality of “being there,” according to Stahel, shows us “the glimmer amid the ashes.” The riveting results from Café Lehmitz alone are well represented here among other notable selections spanning his entire body of work — from debut title Gröna Lund (1973), featuring the visitors, to an amusement park in Stockholm, to The City Diaries.

Solo and group exhibitions throughout Europe and Asia as well as numerous awards have accompanied his singular life’s mission. Included among them are Photographer of the Year 2003 at the International Photography Festival Rencontres d’Arles; Special Prize of the Jury for the exhibit “Exaltation of Humanity” by the Third International Photo Festival in Lianzhou, China; and the 2008 Dr. Erich Salomon Award by Deutsche Gesellschaft Für Photographie from Germany. Since his international debut with Café Lehmitz, he has published about 30 books, a prodigious feat in itself. In 1970, he cofounded SAFTRA, a Stockholm group of photographers.

Petersen, fortunately for his fans, spends most of his time in Stockholm, working underground. As Stahel tells us, “he does not state where he lives, but where his darkroom is…built into the 500-year-old walls of the city.” He works in an analogue fashion, scanning his images from negatives, and uses a small camera — occasionally a Rolleiflex, which he considers to be a “meditative camera with a slower process.”

The Passion

Opening the current monograph, you don’t simply gaze at a Petersen image; you enter it. In his own words, he would advise you to “stuff your intellect under the table, forget it. Things can happen when the ideas you stand for start wobbling under your feet.” Studying Lily and Rosen from 1968, we are caught by the intimacy, the unabashed honesty of the couple. There’s a story here we will probably never know, but that’s okay. The man, bare shouldered, biceps tattooed, curls into the woman’s embrace. Fully clothed, she throws her head back, a raucous open laugh escaping from her lips.

Another shot gives us the same two subjects, with Rosen dressed, leaning aggressively into the table to stare at Lily, indifferent to his attentions as she passively gazes into the camera eye. An older man, stranger or acquaintance, takes up the rear. It’s a moment caught. Petersen, like his predecessor Henri Cartier-Bresson, has captured “the decisive moment,” but has taken it further; pushing us beyond politeness into a place we may not be prepared to enter.

What is Petersen’s response? “You don’t have to fear being afraid.” To him, it’s all part of being alive.

The world of the bistro is not an unfamiliar territory to the roving eye. Early 20th-century Hungarian photographer Brassaï brought his own particular genius to the task and found a number of willing subjects in the Parisian demimonde. If Petersen had stopped publishing with his forays into the life of Café Lemitz, it would have been a worthy stand-alone document — shredding the curtain between the observer and the observed — but there was no retreating. Once he had started to peel away the layers of pretense, the potential artifice of the poser, and went deeper, much deeper, he would find his own genius.

A note to the wary browser: If pretty pictures have the greatest draw on your sensibility, then this photographer will probably not be for you. This is not to say that beauty doesn’t have a place in the Petersen oeuvre, but studying frame after frame, it’s hard not to see that it is the beauty behind the mask — the beauty of the soul for want of another way to express it — that drives him ever onward.

Petersen’s next labyrinthine project was Fängelse (Prison, 1984) at a prison facility in Österåker, Sweden. The photographer calls the theme of documenting these stalemated lives “locked time.” In one particularly moving image, we see an androgynous-looking inmate floating in a bathtub, a passive participant for Petersen’s eye. Forgive the pun, but this is a perfect example of the photographer’s total immersion in his subject.

Two years in one of Stockholm’s assisted-living complexes was another chapter for Petersen that laid open the total vulnerability of the aged or forgotten by society. Ragang till Karleken, (On the Line of Love, 1994) provides a co-mingling of joy and pain. Perhaps the most revelatory part of his involvement with these inhabitants was the realization of his own mortality. The experience allowed him to see “what time is, what it really is. You have to clarify what you want while there’s still time.” Still another prodigious project was Ingen har sett allt (Nobody Has Seen It All, 1995), documenting sessions in a psychiatric clinic. Here patience was paramount — some residents requiring up to six months, according to Petersen, before he could capture their trust.

If subjectivity is the name of the game, the images that resonate for this reviewer may not be the same for another eye. Perusing this collection is a personal journey as much for each reader (and you do “read” these images as much as any literary narrative) as for the creator. I was caught particularly by the attempts — aborted or otherwise — of so many subjects to connect. We see two middle-aged women in underwear in a small room, dancing, it appears, to their own tune. In another shot, we are presented with two women in an embrace with similar floral headdresses — as if costumed for a local production of A Midsummer’s Night Dream — and yet another picture, gives us a pair of presumably identical twin girls confronting the camera with the same indefinable expression. Such images, particularly the latter, are eerily reminiscent of the bizarre investigations of American photographer Diane Arbus.

Occasionally, we are catapulted into a social melee that requires a double-take. A man does splits on a Berlin train platform; a bride sits on the curb of St. Mark’s Square in Venice, the whiteness of her wedding gown in stark contrast to the incidental trash nearby. Petersen is once again giving us a story, but a puzzling one at that. The solitary portrait, such as the pretty Raphael-esque young woman with her trailing locks of hair, has a timeless quality about it and shows, as aforementioned, that innocence and a more conventional beauty is not an unknown commodity for this photographer. I found myself wishing that more such images could be interspersed among the harsh and unforgiving ones.

However, there is no doubt that Petersen has a larger social agenda than the mere artistry of a single pose. He has made it clear that he is not photographing simply what is seen, but what is felt. Interestingly enough, he has also admitted that losing oneself in a book of photographs is a more lasting experience than gallery-hopping might afford. “Exhibitions are more fleeting, they disappear,” he tells us in Persson’s essay. “But books remain and retain another dignity, another presence…you don’t see pictures the same way when you sink into a book as when you’re strolling around an exhibition.”

Still, if this remarkable publication jump starts another round of exhibitions of his works, then we are all the more fortunate to have both options to experience these images. And will the future hold more of the same? As Stahel reminds us, for this photographer “life takes over; photography becomes a side issue.”

What Petersen has finally done for his public is to show that life and a passion for it is the greatest passion of all.

Featured image: PARIS 2006. Photo Credit: Anders Petersen.