‘Women’s Work’: Nice Work If You Can Get It

You remember the familiar lyric by George Gershwin? — “Nice work if you can get it and you can get it if you try.” The work in question is ART with capital letters, a broad and beautiful perspective of women’s art currently on view at the National Academy Museum in New York City. From the iconic and celebrated to the under-recognized, under-the-radar practitioners, this is really several exhibitions in one. These women from the late 19th century to the present day have, as the song says, tried and tried again, and in little and big ways, they’ve succeeded.

To say that this one body of work covers many of the most significant contributions of women artists over the last century, and then some, is not an exaggeration. The National Academy has taken the very pulse of this creative output and it’s alive and well. Pride and persistence co-exist; the refusal to take a backseat to the other gender is very evident here.

Mary Cassatt’s graphic works carry the same extraordinary weight as her best portraits of women and children. The sculptures on display, from Evelyn Beatrice Longman’s Victory to Marianna Pineda’s tragic Defendant, take on a stand-alone integrity in shape and substance, suggesting the permanence of a Bellini or a Rodin. The in-depth look at artists Colleen Browning and May Stevens, whose roles of interpreting their place in the clashes and upheavals of the ’50s and ’60s in opposing ways, gives new definition to the word witness. Finally, the gifts to the Academy from 30 contemporary artists and Academy members strengthen — and in some cases, stretch — our perceptions of reality.

Thanks to the visionary and eclectic nature of the National Academy, women have been students, instructors, Academicians and exhibitors, since the institution’s founding in 1825. It’s only fitting then that such a dramatically diverse collection should highlight one of the greatest American artists, gender notwithstanding, to grace its walls.

Mary Cassatt

When Mary Cassatt was accepted into the first Paris exhibition of Impressionist in 1874, she wasn’t just one of three women so honored, she was the only American. Thanks to a generous gift to the Academy in 1903 by her patrons, the Havemeyers, a set of 12 drypoints are on view in one of the most handsomely appointed, wood-paneled galleries of the museum.

Cassatt has long been renowned for her exquisitely rendered, pastel-colored portraits of women and children, but these finely-contoured images are worthy to be mentioned in the same breath as etchings by Albrecht Dürer or her close friend and contemporary artist Edgar Degas. Tenderness prevails overall, but is never sentimentalized; the subjects ranging from a baby’s back, to a mother nursing, to a seated woman kissing her pet parrot, articulate the moment. Each image conveys Cassatt’s mastery of the pen, her infallible sense of line and contour to portray her subject always present. Each print is enhanced by her ease at including only the exact amount of detail required to convey her meaning. As Gemma Newman noted in American Artist, “Her constant objective was to achieve force, not sweetness; truth not sentimentality or romance.”

Women Sculptors

Upon entering an upper floor rotunda and confronting the silence and power of the 18 sculptures on display, there’s a definite sea-change at work. If the feeling is not exactly Dante’s “Abandon Hope, All Ye Who Enter Here,” there’s a healthy distillation of despair. Marianna Pineda’s Defendant, fashioned in fiberglass on wood, greets the viewer with her bowed head — a stately study in grief. This piece was based on a woman on trial for drowning her infants. We have come 180 degrees from the maternal reassurance of Cassatt’s oeuvre.

Within close range, stands Nancy Grossman’s Gunhead, a sleek bronze head with a pointed gun superimposed over the face. To appreciate the subject matter of this controversial artist who achieved notoriety with her zippered leather heads among other charged works, you have to be willing to take the journey into her dark spaces. As art critic Robert C. Morgan commented in Sculpture Magazine, “There is an undeniable obsession that is at the core of much of the great art of the past, from Caravaggio to Goya to Kahlo. As Grossman explains, ‘you have to be obsessed with what you are obsessed with.’”

But rest assured. There is catharsis in other works here. Alicia is a perfectly lovely bust of a woman’s head in stone by Margaret French Cresson and Elizabeth Catlett’s Fluted Head gives us a highly stylized skull in the German Expressionist tradition of Lehmbruck. Both startle one with their beauty. Eight Horses-Thirteen Legs by Immi Storrs presents a landscape of horse bodies melded together with their equine ears and jaws rearing up from the bronze mass almost as an afterthought. The recently deceased Louise Bourgeois is present with a bronze of indeterminate shoots rising from a bowl, abstract but germinating nevertheless. A minimalist beauty is often at work in this artist’s prodigious offerings, but an occasional sterility as well. Thankfully, Honky Tonk, the quirky bronze statuette by Rhoda Sherbell, gives us a scrawny “say-what?” street-wise girl that’s bound to put a smile on everyone’s lips. Move over, Giacometti.

Colleen Browning: Urban Dweller, Exotic Traveler

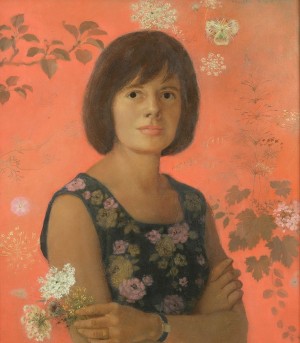

Getting acquainted with the works of Colleen Browning, a most elusive artist who came to prominence as a realist painter in the 1950s, is a little like being charmed by a handful of arresting and attractive individuals at a party. Later, when you recall the encounter, there’s a fleeting glance, a sweeping gesture, a shadowy silhouette, but the real flesh and blood persona remains a mystery. Individual paintings stand alone, in a myriad of styles, with larger themes like urban decay and far-away landscapes and the figures that inhabit them, appearing and disappearing like so many apparitions.

An iconic example of her best known early work is Holiday, depicting a pensive young girl, perhaps from Browning’s East Harlem neighborhood of the time. She studies the street litter at her feet — a random array of garage and confetti amidst the cracked sidewalk and manhole covers dotting the landscape. The child seems contented enough, a winsome little figure in a red dress. Should we read anymore into it? Maybe not, but we probably will. Who is she? Where is she? We may want to delve deeper into the scene but that is hardly Browning’s intent. As Diana Thompson, assistant curator of 19th and early 20th century art observes, the painter’s works “are tinged with the irony of self-contradiction. There is, after all, actually great distance, both physical and emotional, between the artist and these urban subjects she seems to render so sympathetically — from the window of her fourth-floor apartment.”

Another urban setting that manages to unsettle the viewer with the stark tension of its primary blocks of color is Storefront, from 1965. In contrast, a lone brown cat sits before a closed warehouse door. His tiny tan body in the silence of the afternoon gives a sense of desolation, not unlike the isolation in Edward Hopper’s arid landscapes.

(Article continued on next page)