‘Through Her Eyes’: Voices of Ecuadorian Female Athletes

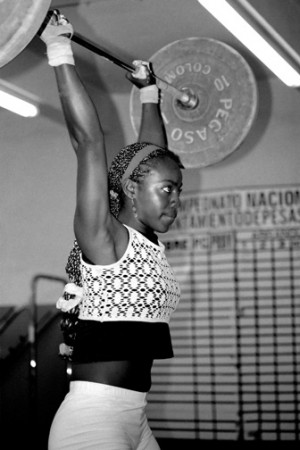

In a black and white photo, stands a tall, mahogany woman with a heavy weighted metal bar lifted above her head, in what can only be described as superhuman strength, captured in a fleeing moment. Her stance shows signs of bodily stability and robustness, and viewers can also catch a hint of emotion in her eyes. There lie glimpses of fight, focus, dedication, passion and genuine spirit. The end goal: triumph. However, another champion weightlifter, Oliba Seledina Nieve Arroyo, does sport for other reasons outside of winning. She weightlifts not only because she loves to, but because she has the support of her family and, perhaps most poignant, to set an example for women and girls out there that females can be more than just a caretaker.

Journalist Elizabeth Stanton decided to document female athletes, like Arroyo, through photographical and translated video interview accounts, all of which had been subtitled in English, for a documentary multimedia exhibition project, which was recently showcased for three consecutive days at the Chicago Art Department. Through Her Eyes partially seeks to encourage females in developing countries to be more active and involved in athletic activities as well as to motivate the self and spirit by depicting the images of those who are keenly involved in sports. Arroyo is exemplary of this intended goal along with the other Ecuadorian female athletes captured by Stanton.

This motivational spirit is certainly further visible in young surfer Andrea Vinueza. In still photographic shots, her fierceness illuminates the moment that she rides the blue-green tides of the murky sea. As she spoke with heart and conviction in her video segment about the waves, one could tell that the high that she experiences from surfing is a love and devotion that will unquestionably lead her to fulfilling her wishes and dreams in life.

“Personally for me in this sport, you have to feel it,” she said. “You have to live it. You have to sleep with it. You have to dream with it. You have to eat with it. In every moment you have to have it with you. This is it. It is the surfer’s spirit, known throughout the world. And the most important thing is the minute you get into that water and you take off. This is a different world.”

One might infer that a community that questions why a woman would do anything outside of being domicile is reflective of inherent societal roles. Motivated to explore this idea after time spent in San Jose, Costa Rica working for The Tico Times, a local weekly newspaper, Stanton felt the importance of creating a space for certain media images to be seen that she felt to be scarce and non-existent. She noticed — particularly in the sports arena — that there was a lack of representation of female athletes. Startled by this observation, Stanton’s sense of curiosity questioned how the deficiency of media coverage on women athletes affects the thoughts and ideals of a society, predominantly one that she found to be rooted in machismo attitudes.

“Every morning at The Tico Times I’d start the day by reading and reviewing the local papers to see what had happened overnight, what was on tap for the day, and what stories we would need to cover or follow up on,” Stanton said. “I recall noticing that there weren’t any stories about women or girls in sports in the daily papers. The back sports pages were always splashed with the colorful shots of male soccer players. And at that time, I remember being struck by the fact that I didn’t see any news, coverage, or photos of women and girls and sports in the papers.”

Ecuador, the chosen region for Stanton’s project, was picked to some degree by chance. In the beginning stages of the project, while she sought out contacts and support in different countries, the Women in Sports Commission (part of Ecuador’s Olympic committee) was the first to reach out and say they were open to working with her. This group also happened to be one of the first South American countries to create such a commission within a national Olympic committee.

“In Ecuador, I had reached out to a woman named Sandra Lopéz, who at the time was head of the press department for the Ecuadorian Olympic Committee. I sent her the proposal showing my interest and said, ‘That sounds great.’ She talked to the president of the committee, Danilo Carrera, [and he agreed],” Stanton said.

They assisted Stanton with housing at the athletes’ living quarters, and also provided her with a list of sport contacts around Ecuador.

“When I first got to Ecuador, my plan was to tell the stories of women in all different athletic levels, socioeconomic levels, and all races. I used those different sport contacts and just wandered around the city talking to people. I didn’t want to just celebrate stories of women who were on that higher level of athletes. I wanted to capture the stories of all women and girls,” she said.

A young girl named Norma Guaranda was one of Stanton’s subjects who represented the everyday, recreational athlete. Guaranda, who plays soccer and is a member of the Quechua community from Bolivar Province, gave her account on the soccer field to Stanton, where she played dressed in a green and yellow jersey.

According to Guaranda’s story, her community does not embrace girls who play sports because they feel it makes them less feminine. In spite of this, Guaranda ignores that particular sentiment and believes that sport is for both genders. Unless she hears a direct order from her parents that she cannot play, she is right out there on the field having fun with her favorite sport because it makes her happy and healthy.

While Stanton was in Ecuador, she spent time all over the country with a home base in Guayaquil where the Ecuadorian Olympic Committee is stationed. She said she traveled to cities, remote jungle towns and everywhere in between, and was on the road for weeks at a time gathering footage for the project.

“In Ecuador, there are various regions aptly named for the climate and terrain: the Sierra, the Oriente, the coast. So, during my time in Ecuador, I would head out to a certain region and travel from city to city and town to town,” she said.

During her time in between, and while in Guayaquil, she explained that she would reconnect with the people at the Ecuadorian Olympic Committee, the women’s commission, and Sandra Lopéz.

“Guayaquil is also where the heads of various sport federations in the country are based, so this was also a place for me to connect with coaches and find out about upcoming tournaments, events, and championships.”

Being that Ecuador is a Spanish-speaking country, and Stanton being someone who is fluent in Spanish, it was much to her advantage when she carried out certain aspects of the project, such as organizing and performing interviews and recruiting ladies to be a part of Through Her Eyes. Due to this, Stanton did not have to rely on translators and was able to be more independent and less restricted in her ventures.

The Through Her Eyes project is a traveling exhibit that has been shown in six Ecuadorian cities and at the South American Beach Games. This past June, it made its way to America. Set to the backdrop of Ecuador’s diverse people and environments, it features 50 large scale photographs and 75 short documentary video profiles of young girls and women alike given the chance to shine and show the world how much the world of sport has impacted their lives, both physically and in everyday life.

Video courtesy of Elizabeth Stanton.

Viewers of the exhibit will encounter females from all around Ecuador and from different cultural groups who live for their sport, whether it is archery, soccer, surfing, karate or something else. Moreover, Through Her Eyes shows athletes in practice mode and game time mode, with Stanton displaying the younger girls in their early years developing their potential through training and learning a sport as well as interacting and being connected with their peers. Per the mission statement, Stanton wants to prove that sports can act as a vehicle for social development by creating new opportunities for women.

The overall reaction from Ecuadorian audiences in retrospect of the exhibit was positive and encouraging, according to Stanton. Also, some of the female athlete participants were in attendance, which was pleasing for her to see.

“I think there was a lot of excitement,” she said. “Some of the athletes that were profiled came to the show, which was very neat and exciting to watch them look at their photographs on the wall or to watch their video.”

One collective opinion that she did receive from onlookers, not in a critical way, was the question of why Stanton would even bother to do a project like this — as if the subject of this project was out of the blue. Stanton said that, in answering their query, she merely explained to them the premise of the exhibit and “a light bulb went off” that she might be on to something.

(Article continued on next page)