The Sleeping Artist: An Interview With Lee Hadwin

Artistic creativity has always been partially associated with the inner workings of the subliminal; a link between fantasy and reality that evolves via unconscious thoughts and emotions that move from one state to the other. Tying the two together with a sizeable splash of talent is an artist who gives a whole new meaning to tapping into one’s subconscious as he draws in his sleep.

Meet Lee Hadwin, 37, by day a nurse, while by night a sketcher. Completely unaware of his actions or surroundings, Hadwin creates intricately detailed black and white drawings of fairies, landscapes, celebrities, and more recently, colorful abstract works — all while unconscious. According to the Edinburgh Sleep Clinic in the United Kingdom, which specializes in sleep disorders and to date has performed several tests on Hadwin, the man dubbed as “Kipasso” appears to be in a trance-like state when these drawing episodes occur. Recently, Hadwin went under more tests for a program broadcasted by Fuji TV in Japan verifying that his mind is in a comatose state, while his body is not. However, the level of sleep he is under remains a mystery.

Hadwin’s uniqueness does not end there. Though sleep-drawing since age four, Hadwin only recently became interested in art, due in large part to his sizeable success and interest from the public. But what remains most intriguing is that during the day, he cannot replicate his beautiful artworks. His talent only comes out at night. Garnishing his house with paper, pencils, crayons, and oil paints, Hadwin has learned to prepare himself for his spurts of nightly creativity, in hopeful avoidance of drawing on tables and walls.

While many skeptics may remain incredulous to his nighttime gift, calling him a hoax, despite Hadwin’s personal documentaries capturing his drawing episodes, gallery owners and the public have expressed an increased demand for his artwork, including several high-profile celebrity figures such as Donald Trump who paid six figures for one of his paintings this past year.

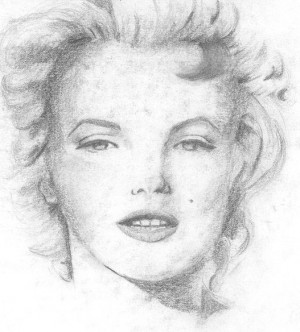

Such steep prices are not uncommon for Hadwin. In fact, he has been previously noted as saying in an article for So So Gay, an online lifestyle magazine in the UK, that at the end of the day “art is art” and “if a person likes a piece of art, it’s up to them if someone wants to spend £10 on a piece, or if someone wants to buy a piece for £40 million, that’s their choice. That’s how I look at art. There’s no room for critics at the end of the day.” One of his most famous sketches, a detailed Marilyn Monroe portrait that undoubtedly captures her signature facial expression as well as her voluminous hair and perfectly placed beauty mark, rightfully entitled The Look, sold for $18,000.

Yet the money he sustains from his creative works, doesn’t solely remain in his possession. According to Hadwin, he contributes a large portion of his funds to charities dedicated to finding missing children and people — one of which is the Missing People foundation – which was spurred by his own running away in adolescence after having come out to his family as a homosexual. By dedicating his time and money, he wishes to provide families and individuals with a level of understanding and support that can sometimes be hard to sustain when it appears that hope has been lost in finding their loved one.

Exclusively for GALO, the artist who never once stepped inside an art school reveals his own theory on his sleep condition, his favorite drawing, and what he is asking of galleries around the world.

GALO: You first began sketching in your sleep when you were four, drawing on furniture and walls among other things, though it didn’t fully emerge into artwork until you were 16. What is your first recollection of this occurrence?

Lee Hadwin: It’s really hard to say. I still, to this day, have no recollection of what I have drawn or painted that night. I used to get up from the age of around four-years-old, as you said, and would sometimes scribble on walls, paper, furniture, and newspapers, and sometimes would just walk around the house in a trance (normal sleep walking activity), which I still do to this day. It was around the age of 15-years-old that the drawings I produced became a lot more intricate, including the famous Marilyn Monroe drawings I do, however, I believe one of these to resemble the pop singer Kim Wilde.

GALO: What surface did you find yourself mostly drawing on until you decided to have an ample supply of sketchbooks strewn across your house like you do presently?

LH: I suppose, I would have to say, the floor is probably the surface I most commonly draw on; then the table or kitchen units unless, of course, I have drawn on a wall, which I have done from time to time.

GALO: How did your family and friends react to this unusual nocturnal talent of yours? Did they embrace it?

LH: My family and friends have always supported me, however, it has been a gradual process; it wasn’t like I got up one morning and started drawing masterpieces. It has been a very long process from just scribbling (so to speak) to what the art world now believes is “art.”

GALO: Your first sketches were mainly of figures and horses. What do you find yourself drawing now?

LH: My drawings have become a lot more mysterious to people, as well as myself, over the last few years as I am not sure what some of them represent — for at least when you draw a figure or animal, you can say, “Well that’s a horse or a fairy” and have some kind of answer. However, I do love the mystery behind the drawings or paintings I now produce.

GALO: Why do you think your drawings have changed both in features and subject matter over time? Is there a pattern that you see repeating over the years? Do you think your own dreams could also be an influential factor?

LH: I believe my drawings have changed over the years as they represent different times in my life, and I believe that they have a lot more meaning now than ever before as I have been using different mediums from crayons to oils. I never did so till a couple of years ago, and now I paint and draw in color, which I never had done before.

(Article continued on next page)