Our Savior of the Moral Dilemma: John Patrick Shanley Builds a ‘Storefront Church’

There is no playwright alive who understands human motivation and its moral consequences better than John Patrick Shanley. His trilogy, Church and State, began with Doubt, about a war between a controlling Mother Superior and a beloved priest with a secret, followed by Defiance, the story of an army officer who promotes a soldier based solely on race but has his own closet full of skeletons. Now, rounding out the group is Storefront Church, a situation set squarely in the middle of the economic downturn, focusing on a poverty-stricken Bronx woman about to lose her house to the bank and what happens to the conflicting agendas of everyone involved.

The play could have easily been entitled Debt, as everyone in it owes something to someone, whether it’s money to a bank, obligation to a higher power, or respect for a parent’s moral legacy. Jessie Cortez, an elderly Caribbean woman married to an impoverished Jewish accountant, Ethan Goldklang, is eight months behind in her mortgage payments. Ethan pays a visit to the bank officer, Reed Van Druyten, who, himself, has obviously been mangled by life’s twists and turns. His face is half paralyzed, he is blind in one eye, and he creepily keeps spouting bank protocol like a fractured robotic guidebook. In the middle of trying to appeal to the man’s heart, Ethan himself has a heart attack and falls to the floor (no, he doesn’t die). In the wake of this incident, Jessie appeals to Donaldo Calderon, the Bronx borough president and son of her best friend, telling him, “Your mother said you would help.” It turns out that the issue with the loan is a second loan encumbrance of $30,000, which Jessie took out to help a minister open a storefront church in her home. These churches, prolific in poor neighborhoods, are makeshift but relentlessly sincere. The minister, thus far, has done nothing, nor has he paid Jessie back a cent. Donaldo is in the process of building a huge neighborhood complex financed by the very bank that holds Jessie’s mortgage and is, coincidentally, meeting with the CEO, Tom Raidenberg, the next day. He squirms and squeaks as Jessie implores him to help, saying it would be a conflict of interest, more worried about his urban project failing than Jessie — until he is told that his own mother is a co-signer on the loan.

The play interweaves the relationships of Jessie and her husband, Ethan, with Donaldo, Reed, and Tom, the soulless, greedy CEO of the bank (who has a wonderful scene where he hungrily devours a gingerbread house intended for his son during a conversation with Calderon), and, last but not least, Chester Kimmich, the Malcolm X-like minister with no ministry. In perhaps the most pivotal section of the play, Donaldo goes to the ersatz church to confront the minister, who at first asks him to leave but, as Donaldo holds his ground, is coaxed into admitting that life has thrown a “black hole” in front of him and he can’t find his faith. They engage in a long discourse that volleys between the actual situation (the defaulted loan) and the idea of a higher power and losing one’s way, straying far from a moral code, and what’s acceptable in the name of social action. By the end of this, Donaldo doubts his own ambitious motives in life, and is haunted by the memory of his own late father, also a minister. Chester, on the other hand, has been convinced to give his first sermon that Sunday. It’s at this simple gathering that peoples’ true colors show. The weak find the strength to speak their truth, the strong are revealed as morally corrupt or bankrupt, and while Jessie’s immediate problem is solved, larger ones have opened to different degrees for everyone. The most affected is the aspiring politico Calderon who either cannot go back to the steep career ladder he had only just started to ascend or must find a different way to climb it.

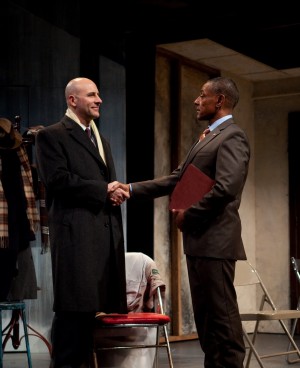

There is barely a misstep among this group of veteran actors who form a near-perfect ensemble. Tonya Pinkins, a Broadway mainstay, is luminescent as the play’s moral center, a role in some ways similar to what she played as the maid in Tony Kushner’s Caroline, or Change. As her husband, the impoverished Jewish accountant, Ethan, played by Bob Dishy has all the big laugh lines but also the biggest heart. Zach Grenier, familiar from decades of acting work including the fabulous Deadwood on HBO and a myriad of films, lets his body unfold artfully in tandem with the telling of his backstory, and his face seems almost normal by the play’s finale, as though he has dealt with his demons — he defines superb acting here. Jordan Lage, as the greedy bank president who chooses cronyism over justice, is appropriately cut, dried, and greedy with an eye unwavering from the financial ball, willing to pay the small price of forgiving Jessie’s loan for having Donaldo owe him a considerably larger political debt. The minister, played by Ron Cephas Jones is perhaps the least believable of the group, and it is not completely clear why he suddenly shifts gears after his talk with Donaldo apart from the fact that the play would go nowhere if he didn’t. An austere presence, it’s also difficult to understand why Jessie has been so forgiving of his inaction in building his church, except that she values God above money. In the end though, the magnetic Giancarlo Esposito as Calderon is the shining star of the show, swaggering and self-confident at the get-go, wavering slowly across the play’s timeline until he becomes a completely different and more human character, ready to testify not only in front of community boards but also before God.

Yet, in the limelight of the cast, the director himself should not go unnoticed. Mr. Shanley is from the Bronx, and apparently came up with this idea while walking through the old neighborhood — a perfect fit for a playwright who has been referred to as a renegade choirboy. His direction is pitch perfect, with the single exception of the outcome of the first meeting between the preacher and Donaldo, but perhaps some vagueness was intended there, a leap of faith. There are a few nips and tucks needed in the piece, but, for sure, less complete product has been a mainstream hit before. It’s a shame that Storefront Church has such a short run at the Atlantic; nevertheless, it is great to see the superb renovation of the Linda Gross Theater, one of New York’s off-Broadway jewels, put to good use. The hope is that, in this time of tumultuous change, economic woes and shifting moral attitudes, more people will soon be able see Storefront Church and garner some inspiration, perhaps even finding credibility in a path that includes, at least, a little bit of faith.

The play runs through June 24 at The Linda Gross Theater in New York City at 336 W 20th St. For ticket information and showtimes visit www.atlantictheater.org or call 212-279-4200.