Art School Confidential

Bill Richards already had a major in speech communication paid for by a generous state scholarship when he decided to enroll in art school at the University of Georgia. A talented cartoonist, who had been drawing political comics for the student newspaper for several years, Richards hoped to gain skills and experience in graphic design. Now unemployed and struggling to find work, (“Everybody’s a graphic designer because everybody has a computer,” he says), he wonders whether the three years out of pocket tuition will have been worth it.

“If I had done it first on HOPE (a full ride scholarship for residents of Georgia), I would say ‘yes,’” Richards said when asked if he thought art school was a good value. “But given where I am right now, it’s not looking too good.”

With the cost of college education rising and a punishing job market, artistic and talented young people may be considering whether to pursue an art degree or rely on experience, apprenticeships, or raw talent.

Sandi Hall, a successful portrait artist in Burlington, N.C., graduated from the Savannah College of Art and Design with a Bachelor’s in photography and a minor in painting. While she rarely uses the darkroom skills she learned in class, Hall said she would not trade her experience at SCAD for anything. In fact, she would enthusiastically recommend art school to an aspiring art student.

“You are able to learn the fundamentals of art; where it came from, why, and different processes,” Hall said. “I believe the fundamentals of art are very important. Knowing why and how things work, the way they do help you further understand what you are doing through your art, and help you grow in your expertise of that art form.”

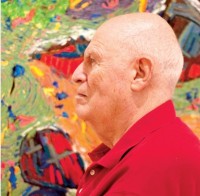

Professor Emeritus of the University of North Carolina’s art department, Marvin Saltzman, taught art at the university level for over 30 years. Saltzman, a self-described unconventional teacher, has advised a plethora of highly successful artists working in the market today. With prestigious positions ranging from head of city planning in New York City to founder of a multi-disciplinary design firm; it’s hard to argue with the outcomes of his students. But Saltzman is critical of many art school practices in place today.

Some years ago, Saltzman stood in front of a classroom full of his students. They had just completed a standard assignment, and he had released them onto a picturesque section of campus, asking them to sketch a scene they found there. He then requested that they hold up their drawings with two hands and rip them right down the middle.

“You may destroy your own work,” Saltzman said, “No one else has that right.”

Saltzman shunned many of the hallmarks of a traditional painting class.

“In my years of teaching, I never took a brush from a student’s hand. I never set up a still life.”

Instead, he put the onus on the student. “What do you want to paint? What do you want to say?” Saltzman recalled asking.

“There is nothing wrong with art schools,” says Saltzman, “If they are taught well. The tragedy is that they are often not taught well, and students don’t know any better.”

The way Saltzman sees it, the majority of art students shouldn’t be in art class.

“Once you’ve learned the process, you don’t need any more of a class. You need a critic, someone whose eye you trust,” Saltzman said.