Where They’ll Be When They’re Gone: ‘The Last Safari’ through Two Africas

Africa. You read the word and a mesh of timeworn images pours into your head: An exhausted woman clutching her emaciated child, a dusty, crammed refugee camp in Somalia, the horror of Rwanda — starvation, indigence, and violence. The positive associations are more to do with wildlife and topography than people.

In their new documentary on the tribes and peoples of Africa’s Great Rift Valley, The Last Safari, director Matt Goldman and photographer Elizabeth L. Gilbert invite you to take a closer look at one, narrow ribbon of Africa: a road that begins in Nairobi, Kenya and after a brief detour in Maasailand, winds northward to Lake Turkana (which kisses the Ethiopian border). Along the way, they both redress and confirm many of the narratives surrounding Africa, while presenting an intimate portrayal of cultures usually relegated to postcards and travel brochures in our corner of the world. They ask delicate, incisive questions about the role of traditional culture in a world permanently mobilized for modernity, and they do so with great care for their material. Thankfully, they don’t try to hurl the answers at you, either.

Gilbert has been photographing Africa for over 22 years. At the beginning of her career, she captured lacerating images of the Rwandan Genocide, as well as civil wars in Somalia, Sudan and Zaire. Unlike many who’ve committed themselves to this unhappy task, Gilbert didn’t see the value in it at the time. She lamented the lack of impact her pictures were having, and says in the film, “After decades of covering war, I learned one thing: my pictures really weren’t helping anybody.” So in 1998, she stopped doing it with only a vague idea of what she wanted to do in its place, “I wanted to leave Africa having pointed my cameras at something more…beautiful.” She spent the next four years traveling through Maasailand, capturing glimpses of vanishing Maasai culture. This experience culminated in the publication of her first book in 2003 — Broken Spears: A Maasai Journey. What followed was an even more ambitious effort — Tribes of the Great Rift Valley, which was published in 2007 and spans 3,500 miles, documents 25 tribes, and took more than two and a half years to complete. This longstanding personal attachment undergirds every aspect of the film, and Gilbert’s relationship with her subjects is affectingly genuine.

In some ways, The Last Safari is a natural successor to Gilbert’s efforts as a photographer. The knowledge that many of the tribes she’s photographed are rapidly disappearing has created in her a sense of urgent purpose. She wanted to compile a record of their ceremonies — weddings, rites of passage, and so on — for the benefit of the tribes themselves. This compulsion was the impetus for her two books, meaning she did more than simply take the pictures and make a few dollars off of them — she recorded, in luscious detail, the memories of Africans whose cultures are on the cusps of their codas.

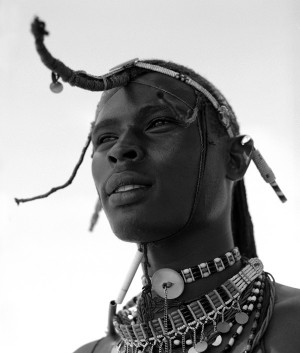

This process brings to mind a famous Chinese proverb — “The faintest ink is better than the best memory” — and Gilbert’s pictures are anything but faint. “I wanted them to have a document about this part of who they were that they could refer to in years to come,” Gilbert says, “But it wasn’t my desire to see people live in a museum.” If The Last Safari was a mere montage of Gilbert’s photography coupled with Goldman’s cinematography, it’d still be well worth watching. But it’s more than that — it tells a series of captivating stories with a seamless combination of photography and film, and it captures the changing zeitgeist of modern Africa through the perspectives of Africans themselves. For example, there’s the shot of a Samburu warrior named Patrick as he is today and his picture on the cover of Tribes of the Great Rift Valley almost a decade ago. Patrick thumbs through the book with a mix of nostalgia and intrigue before he’s interrupted by a call on his cell phone. Whereas Patrick is still a warrior, another of Gilbert’s friends — James Mpusia — is now a Christian and father of two living a suburban life away from the bush. The juxtaposition between young James in his circumcision headdress and today’s James in a white polo shirt holding his son is, in many ways, an encapsulation of the film’s main theme: modernity versus tradition.

So not only did she compile these pictures for future generations, she took them back to the places where they had been taken and presented them both to individuals and to entire villages on a cinema screen, often to great acclaim, sometimes to indifference, and other times to a curious mixture of engagement and self-interest (the crew occasionally had to pay village elders to show the slides). The Last Safari is a chronicle of this adventure, and after almost a decade and a half of study and experience, there are few guides more capable than Gilbert.

Goldman, on the other hand, isn’t exactly accustomed to safariing. In 1999, he founded a Brooklyn-based production company called Akjak Moving Pictures, where he has produced, edited, and directed a range of short films, music videos, and commercials. His first short film, Broke won the award for “Best Editing” at the Brooklyn International Film Festival in 2000. His second short, The Perpetual Life of Jim Albers was featured at the Sundance and Rotterdam Film Festivals and received “Best Editing” at the Brooklyn International Film Festival as well as “Best Digital Film” at the Santa Cruz Film Festival in 2003. The Last Safari is his first feature-length film, making its level of polish and potency especially surprising.

There may be some overlap between your idea of a place and the reality of it, but the fringes are bound to surprise you in both directions. It’s the exhibition of these fringes that makes The Last Safari such a breathtaking exercise in ethnographic study and human interest. For example, you might know that the process of becoming a Maasai warrior is fraught with difficulty, but it’ll likely surprise you to learn of the requisite seven years of service, the consumption of blood, beer and milk from the freshly sliced neck of a bull, or the reality of an experience so intense that it puts the warriors in a “trance-like” state when they return to the village. Or perhaps you know that much of modern Africa is becoming increasingly indistinguishable from many Western countries. But you may still find it curious how the film crew — folks from a Nairobi-based group called Full House Productions — is almost entirely antithetical to the film’s primary subjects. “In some ways, they were more American than Americans,” Gilbert says of them. The Last Safari covers this entire continuum, and it does so with a rare blend of honesty and visual splendor.

A few of the darker aspects of modern Africa are on display as well. Africa is a hard, pitiless place: nine of the ten countries with the highest infant mortality rates are in Africa, as are the vast majority of countries with the lowest life expectancy. The threat of violence is real and persistent, demonstrated by the ghastly carnage wrought by the recent Al-Shabab rampage at a mall in Nairobi. And while it doesn’t dwell on them for long, there are two violent episodes in The Last Safari: the first happens off-camera when Gilbert and one of the drivers (Martin) are intercepted by gun-toting men (likely Turkana warriors-turned-vagabonds) on the road; the second is in South Horr when most of the crew members find themselves awakened in the middle of the night by gunfire in town. A robbery was in progress.

(Article continued on next page)