Where They’ll Be When They’re Gone: ‘The Last Safari’ through Two Africas

However, The Last Safari doesn’t just toss these incursions on screen to heighten the sense of tension and drama — they serve as vehicles for the film’s broader theme: the dissolution of culture and its ramifications. For example, after the robbery we find out that the perpetrators were “murrans” (warriors) who’ve become redundant in their tribes. “The hotel owner tells me that this is all too common,” Gilbert says, “And that ‘murrans’ live in a changing world that no longer needs them. It’s not unusual for them to take to a life of crime.” And suffer no illusions about the film’s law-abiding subjects, either — for Maasai women, the ugly practice of genital mutilation is compulsory. If the charge of cultural imperialism is to be leveled, so be it — female genital mutilation is a pointless, dangerous blight, and it should become an unpleasant memory as soon as possible.

If one criticism can be leveled against The Last Safari, it’s the decidedly detached way in which these difficult questions are approached. The film is admirably bias-free, and this is part of what makes it so compelling. But “bias-free” and “argument-free” are different things. Of course people should have every right to live as they do and generate their own meaning, so long as their existence doesn’t threaten anyone else. But one question will be implanted in your head from the very beginning: On balance, is modernization good or bad for the film’s subjects? Gilbert would probably answer, “Neither.” Or perhaps she would answer, “Both.” Unfortunately, you can’t be too certain because her opinions are only vague echoes throughout the film.

Gilbert mentioned a recent Maasai initiative to protect their land from encroachment, but if this is merely an attempt to stave off the inevitable, might it be counterproductive? Yes, people should be free to choose how they want to live. But a hermetic life as a tribesman in rural Kenya is a form of unfreedom — their lives are often brutal and short, and information about alternatives is hard to come by (though this is changing). At just under an hour and fifteen minutes long, The Last Safari had ample time to look at a few of these questions qualitatively. An attempt to do so would have made it a more comprehensive meditation on the fascinating questions it poses.

Still, the filmmakers’ refusal to interject left the film more open to audience interpretation, which some viewers will consider one of the film’s stronger elements. One theme of the film — the experiential clash of divergent ways of living — didn’t call for commentary. Much of Africa is in a state of transition. It’s a mystifyingly heterogeneous place where the trappings of modernity run alongside the (sometimes crumbling) pillars of tradition, occasionally weaving throughout or around them. Four of the ten fastest growing economies in the world are in Africa (Libya, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Ghana), and as the film crew demonstrates, globalization and mass communication have irrevocably changed countless social and cultural institutions.

One of the cleverest decisions taken by Gilbert and Goldman was to highlight the film crew as members of an increasingly Westernized and homogenized urban culture in Kenya. Their opinions on many of the traditional cultures range from polite incredulity to thinly veiled disdain, demonstrating the dynamic nature of contemporary Africa. People in the West bizarrely tend to refer to Africa as one, uniform entity — a major mistake to begin with, but one that may be unavoidable when it comes to an entire continent rife with seemingly intractable problems. But the reality is a vibrant array of peoples and individuals who are rapidly conforming with (and sometimes confronting) the times, and about whom no all-encompassing statements can be made.

In a 1984 BBC interview with Germaine Greer, British novelist Martin Amis said, “In shorthand, money is the opposite of culture…” It was certainly on his mind at the time, as they were discussing his then-freshly published novel, Money. He goes on, “…money is the first value that gets to you, unless you’ve got culture to stave it off.” While the real dichotomy may not be quite so stark, the corrupting influence of money is hard to deny. Then again, culture is a nebulous word, and Amis might have taken unjustified liberties with it.

Near the end of The Last Safari, the crew has a pair of disheartening encounters. First, they’re accosted in the street by a band of people who think Gilbert has made money off of them. They pound the hood and windows of the Land Rover and only disperse when Gilbert hands one of them a wad of cash. Then, upon arriving at Lake Turkana, Gilbert is told that the locals refuse to watch her slideshow if they aren’t paid beforehand. Gilbert says, “If we have to pay people to look at this thing, I feel kind of stupid. I just want to go home.” But she adds, “I think…I don’t know.” Matters deteriorate further when a group of villagers congregate, start bouncing up and down and chanting for no apparent reason. Martin says, “They think we are tourists and we’re gonna give them money. I don’t think it’s real.” Gilbert replies, “You know, I spent years trying to document genuine, vanishing culture. And I find myself at the end of this journey being given a tourist dance, which is the thing that I sought to avoid.” But then she has a flash realization — yet another moment of nuance in a film so wedded to it, “In a way this is another truth. This is another reality. And in some ways, I think what I did was a fantasy.” Resigned to the cold reality of the matter, they decide to pay the local elders and go ahead with the show.

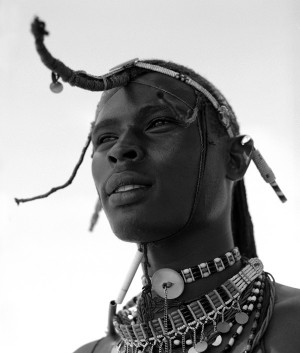

In keeping with Gilbert’s revulsion at the idea of people “living in a museum,” it must be said that the “genuine” customs on display in The Last Safari are more than colorful relics of humanity’s adolescence. The sheer range and depth of human experience is too complex to be regarded as a simple progression, with each change bringing about happier, healthier people. The images of Maasai warriors during and after their Eunoto is both engrossing and a little unnerving — in that moment, the warriors know exactly who they are and what purpose they serve — a sense of identity that modern society doesn’t often provide. Such an experience shouldn’t be considered a charming little quirk of 21st century humanity. It’s a distillation of everything we value and seek to cultivate — community, a sense of shared and individual meaning, and the full expression of the self — arbitrary as it all may be. But by showing the ways in which other Africans have embraced openness and change, the The Last Safari also demonstrates the steep price traditional cultures have to pay. Much comfort, safety, and health must be sacrificed to live in the bush and the sense of meaning and affirmation mentioned above is indistinguishably entwined with hardship. This entire ballad of suffering and transcendence, change and resistance is happening right now, but it will almost certainly come to a close soon. We’re fortunate to have glimpsed such a bewildering, bewitching episode of history before it’s finally extinguished by the slow march of time, and we can thank Goldman and Gilbert for bringing it to us with such integrity and skill.

Rating: 3.5 out of 4 stars

Trailer Courtesy of: Matt Goldman/Pandora Multimedia Productions in association with Akjak Moving Pictures.

Featured image: A warrior from the film “The Last Safari” by Matt Goldman and Elizabeth L. Gilbert. Photo Courtesy of: Pandora Multimedia Productions in association with Akjak Moving Pictures.