Painting In Fragments: Artist Colin Chillag’s Illusionistic Work

Portrait painting is nothing new. And yet, in the hands of Arizona-based artist Colin Chillag, this genre takes on novel properties.

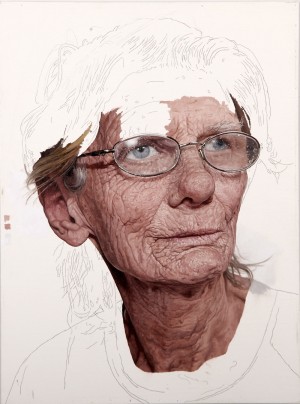

Colin’s portraits are a curious mix of hyper-realism and abstraction. Focusing on the head and upper-torso of an individual, Chillag renders in incredible detail every inch of the subject’s face — a tobacco-stained tooth, a deep-set wrinkle, or an unruly hair. In a seeming incongruity, though, above and below this almost photographic depiction, lies blank space. The paintings are often left unfinished. Or, in some cases, they are painted over with paint splotches or other similar abstract details.

In one of his portraits (which shows an older woman wearing glasses), the 41-year-old artist even leaves a layer of his preparatory sketch uncovered. In this portrait, the woman’s neck and lower face are completely filled in with paint. To the contrary, the top of her head and lower torso are nothing but a series of light grey pencil marks.

Evidence of the artist’s hand abruptly breaks the illusion of realism in the middle of the canvas.

This juxtaposition between realism and abstraction, however, is not a contradiction, according to Chillag.

He explains that the disparate elements of his paintings actually compliment each other and fit into his overall artistic vision. With his portraits, he is not aiming for realism, he says. Instead, he hopes to capture the processes of interpretation and consciousness we experience when attempting to understand the world around us.

This is a message he conveys primarily by leaving his paintings unfinished or deconstructed. Chillag wants viewers to be able to see his artistic procedure — the way in which he goes about understanding and recreating an image.

“My intention is to make this process open and available to viewers at every level,” he explained. “I allow the pencil sketch to remain visible as part of this process, and I even go so far as to incorporate the palette into some of the paintings.”

“So, while I engage in a highly illusionistic form of painting,” he added, “I have no real desire to complete the illusion by finishing a painting.”

He also demonstrates the illusionistic and personal nature of painting by assigning more detail to certain parts of his canvas than others. In the aforementioned portrait of the older woman, for example, there is a great imbalance between the amount of attention and detail given by Chillag to the woman’s face versus her torso. This mirrors the actual way we receive images.

“I think the disparity in attention I give to one part of a face over another has a rough correspondence to our natural process of perception and to consciousness itself,” he says. “What I simply offer is a roving consideration of the landscape of the human face.”

Apart from this, he insists that there is no other “narrative or implied meaning” behind his paintings.

Rather, he sees his role as an artist to be a mere observer, “I started to view my job…to be less about expressing personal thoughts, or feelings, or opinions, and more about a simple and steadfast observation.”

Despite the fact that his portraits lack an explicit message, he “trusts that there is some value in them, if only because of how rare [they are].”

He also points to the fact that each painting requires an intensive amount of work. Painting each image is a grueling process that can take up to two weeks. And, according to Chillag, he “might [even] spend a whole day painting a single eye.”

The Syracuse born artist has been interested in art ever since he was a teenager. At 13-years-old, he decided he wanted to be a painter, claiming that it was a “completely uninformed” decision.

And yet, as it turns out, it was also a “fortuitous” one.

Chillag has devoted his life to painting, and found success. He trained at the San Francisco Art Institute, and his work has been featured in museum and gallery shows across the country.

But though he has been painting for years, he feels that his portraits represent a new direction in his art.

“These paintings represent a major shift in my work and life,” he says.

This shift is due to a couple of new interests. The first of these was an interest in meditation practice and Buddhism (primarily, Zen Buddhism). He explained, “In some ways I view these paintings as a form of meditation in activity.”

His other burgeoning interest was, he said, in “the field of phenomenology.”

Though his portraits mark a turning point in his career, Chillag has treated philosophical themes in earlier works too. In 2008, he displayed a series representing different scientific fields at the Angstrom Gallery in Los Angeles.

In a way, these works also touch upon questions of perception and the transmission of knowledge.

The Angstrom paintings show how fallible so-called scientific ‘facts’ can be. Chillag was interested in representing, “invented or erroneous” information that science sometimes produces. These mixed-media works capture “the interplay between neutral observation, and invention or imagination.”

Just as his portraits (representations of ‘real’ people) are skewed by Chillag’s own perception, so too can science be affected by the whims, imagination, or personal opinions of scientists.

Overall, Chillag’s body of work culminates in destabilizing the very notion of realism.

“In actuality any good realist painting requires an extreme degree of inventiveness,” he says. He believes that, “any communicable form is necessarily an invention and to some degree obscures the direct experience which it intends to communicate.”

And his work seeks to remind us (sometimes vigorously, sometimes whimsically) of this message, namely, that all human experience is inflected by personal perception and consciousness.