Lewis Hine: Photographer As the People’s Prophet

This profound attention to the child’s plight resonates in the work of wartime photographer David Seymour, aka Chim, who must have been inspired by Hine’s body of work when he captured in the ’40s his young orphans moving among the rubble of war-torn Europe. Hine’s work was undoubtedly a springboard for such socially-committed individuals. (A review of a major ICP exhibit, David “Chim” Seymour – The Invisible Man appeared in GALO’s online pages in March of this year.) Hine traveled to Europe only once, in 1918, as part of the American Red Cross survey and in France, Serbia and Greece found a fount of inspiration in the young victims he encountered.

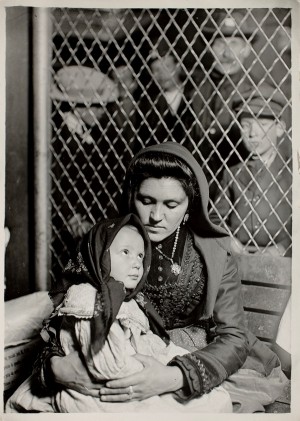

Hine’s group portraiture was just as riveting. In his Tenement series, two women sit with their charges in a tenement alleyway in one instance, with barely enough space to occupy. But they take in the shafts of sunlight with clean, fresh, even hopeful faces. In a group portrait of a cotton widow and her family, it is impossible not to conjure up the later dustbowl images of the great Walker Evans. Hine has placed a cotton widow and her family in front of their ramshackle home. Nine children are lined up single-file, all barefoot except for the oldest girl. Their clothes are dirty and worn, but it is the smile on one of the little boy’s faces that captures the heart. Hine was a master at capturing the natural buoyancy of childhood in spite of overwhelming odds. Viewers will find a number of publications that featured Hine’s photographs, dealing with alcoholism, disease, and the practice of employing immigrant families to work at home, doing piecework for the garment and food industries. He was a regular contributor to Charities and the Commons, the most important philanthropic journal in the United States. Hine received a byline for his work, which was rare at the time.

Documenting the construction of the Empire State Building was no small task. Commissioned to photograph the entire project, it became during the Depression a beacon of progress in difficult times. This effort became a mainstay of his book project, the 1932 Men at Work. One of the most stirring images is Icarus Atop Empire State Building. To get such lofty depictions, Hine had himself suspended 400 meters above Fifth Avenue.

What would have made these exhibits even stronger, as was accomplished in the aforementioned Chim retrospective, is more of the personal history of this photographer. As Mason Klein reported in his notes for The New York Photo League’s The Radical Camera, Hine was “forced to go to work in an upholstery factory after his father was killed in an accident.” He eventually became a bank clerk and was persuaded by a co-worker professor to continue his education. After a stint at the State Normal School in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, he transferred to the University of Chicago and was influenced by the progressive educator, John Dewey. After achieving a master’s degree in education at New York University, he left teaching to concentrate on what the ICP’s exhibit notes tell us became his obsession — “the visual side of public education.”

According to Alison Nordström, curator at large of the department of photography at the George Eastman House, by the late ’30s the timbre of the times was changing. Social reform and photography were becoming separate worlds and the government agencies of the New Deal found Hine “difficult and old-fashioned.” He had his champions in photographer Berenice Abbott and art historian Beaumont Newhall, who saw Hine as a “spiritual ancestor” of Walker Evans. The need to “bear witness” among photographers in the early 20th century began, according to Klein, with Hine, “with the heroic efforts of an extraordinarily modest man,” who died in poverty in 1940.

Hine was a man of singular ambition, with a highly developed sense of social consciousness. ICP has done an exemplary job of bringing the social concerns in Hine’s images into the spotlight for today’s audience. Though his work can stand alone, turning the lens on the man behind this incredible output would help us to understand even better his amazing contribution.

The joint exhibitions, “Lewis Hine and The Future of America, Lewis Hine’s New Deal Photographs” will run through January 19, 2014 at the International Center of Photography in New York City. The ICP is located at 1133Avenue of Americas, New York, NY 10036. For more information please visit http://www.icp.org/ or call 212-857-0000.