Into the Void and Beyond: ‘Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925’

Such serendipitous encounters were not that unusual and often were a life-saver in tumultuous times. When the Russian Revolution brought an end to parental support, Sonia and Robert Delaunay would design sets and costumes for Serge Diaghilev, the famed dance impresario who helped bring a kind of artistic immortality to the dancer Waslaw Nijinsky and composer Igor Stravinsky. A welcome inclusion in this exhibit are several crayon and pencil studies by Nijinsky (Arcs & Segments: Lines + Pencils) that show an elegance with geometric forms perhaps unknown by his fans in the dance world. Another example of social mingling leading to productive output is Francis Picabia’s Dances at the Spring. This is a large, compelling work utilizing muted roses and warm browns, a palette inspired by Picasso’s own Rose period but also, as the wall notes tell us, by a road trip the artist had taken with Claude Debussy and Apollinaire.

By such a broad global inclusion of artistic outpouring, a few will predominate and others will inevitably receive a passing nod. Kazimir Malevich, among the Suprematists, and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Giacomo Balla, among the Italian Futurists school, make a grandstand play for our attention. Malevich could be anointed the grandfather of minimalism after viewing his black and red square painting entitled Painterly realism of a boy with a knapsack color masses in the 4th dimension. Only the title begs our forbearance. With a bit of imagination, the smaller square could be the knapsack in question, but this reviewer couldn’t help but feel that the artist was having a laugh on the viewer with that description!

Balla, in particular, was obsessed with the temptations of speed. Speed is of the essence in this new century and why shouldn’t art reflect the notion? Balla’s Abstract Speed + Sound is a riveting example of a painting that seems to jump out of the frame with dizzying results. Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell from England’s Bloomsbury set rest quietly in their corner, in danger of being overlooked among the splash and dazzle of the Delaunays, Kandinskys and Ballas. Grant’s Interior at Gordon Square is not at first glance his most inviting work, with its muted olive greens, but the overall composition pulls us into his intended interior.

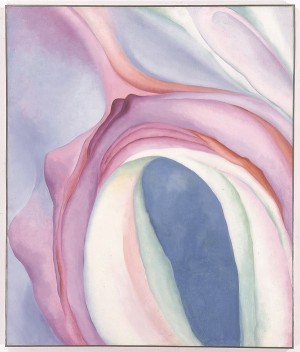

Americans Marsden Hartley, Georgia O’Keeffe, Paul Strand and Alfred Stieglitz get their day in the sun, with Hartley’s Provincetown Abstraction, one of many canvases that capture our attention. It is a whimsical dance of triangular shapes that departs from the flag and Swastika infused designs we associate with much of his work. O’Keeffe’s Grey Lines with Lavender and Yellow is a gorgeous undulating work that lets the viewer revel both in its serenity and sensuality. Her Pink and Blue No. 2 appears as a giant organism seen through a magnifying glass. Photography highlights include Stieglitz’s Music—A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs and Strand’s Porch Shadows, which in its grid of lights and darks shows a master’s touch.

Sculpture offerings seem to arbitrarily punctuate the exhibit rooms, such as Constantin Brâncuși’s Endless Column as well as Max Weber’s Air-Light-Shadow, both worth more than a cursory glimpse. The latter manages to put abstraction into concrete terms with a compelling series of triangular planes firmly embedded in their base. More hypnotic is Marcel Duchamp’s Rotary Demisphere. In this precision optical experiment, the viewer is advised to stand a meter away from the center of the piece as his painted papier mache design on a painted plexiglass disc pulls the eye into its vortex. The result is something like a giant blue and white worm undulating toward its victim. It’s a conversation piece for all ages.

If the visitor does not object to surrendering a picture I.D. for an hour or two for a free audio guide, it is well worth the effort. As a comprehensive centennial exhibition, organized by over 350 works in a broad range of mediums — including paintings, drawings, prints, books, sculptures, films, photographs, recordings, and dance pieces — it offers a sweeping survey of a radical moment when the rules of art making were fundamentally transformed. It is, literally, history in the making. Revolutions, world wars, and yes, cultural upheavals change the way we live and think.

(“Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925” will run through April 15, 2013 at the Museum of Modern Art, located at 11 West 53rd Street, New York, NY 10019. For more information please visit http://www.moma.org/or call 212-708-9400.)