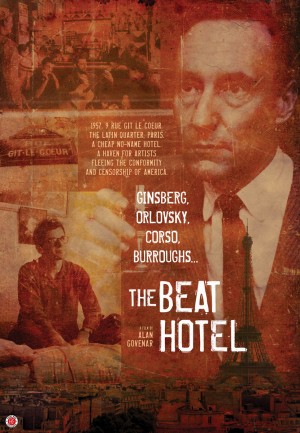

The Beat Generation in Paris: A New Film from Alan Govenar

William Burroughs is writing his incendiary Naked Lunch, Gregory Corso is creating his “Bomb,” a bombastic poetic send-off to the nuclear age, and Allen Ginsberg is cooking up his next Whitmanesque paean to love, in the arms of his life partner, Peter Orlovsky. We’re in New York’s East Village or San Francisco’s North Beach, right? Wrong. We’re in the heart of the Latin Quarter in Paris and the Beat Generation has come home.

In film director Alan Govenar’s new film, The Beat Hotel, we are catapulted back to the heady, hedonistic years between 1957 and 1963. Militarism, materialism, and sexual repression are in full sway, and some of the brightest and bravest are fleeing the good old U.S. of A. for more welcoming shores. Chief among them is Ginsberg, fresh from the obscenity trials surrounding his poem “Howl”: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness/Starving hysterical naked/Dragging themselves through the Negro streets at dawn/Looking for an angry fix.” Over 50 years later, the words still have the power to chill the bones. It is little wonder that Ginsberg, and the rest of these talented vagabonds, looked for a new address.

The film opens with Scottish artist Elliot Rudie (a former resident of the hotel), tracking down Harold Chapman, the legendary British photographer of the Beats, to a small seaside town in Kent, England. Chapman is a jolly, non-assuming sort, who lived in the hotel attic and, according to Ginsberg, “Didn’t say a word for two years” because he wanted to remain invisible — a visual voyeur to literary and artistic history in the making. Through the seamless editing of film editor Alan Hatchett, the film quickly transports us on our journey to 9 Rue Git Le Coeur, where for ten francs a night, Madame Rachou offers up squalor and sentiment in equal measure.

Crammed into closet-size rooms, Chapman recalls that this creative sanctuary housed “an entire community of complete oddballs, bizarre, strange people, poets, writers, artists, musicians, pimps, prostitutes, policemen and everybody else you could imagine.” We are reminded that the police often turned a blind eye to the proceedings, given their preoccupation with the French Algerian war of the day. A 40-watt bulb was considered sufficient light for each tenant, and a once a month cleaning was the tenant’s option. Odors abounded—cuisines of every nationality concocted on miniscule hotplates, combined with the daily smells of hashish and urine from the darkened doorways and stairwells.

A fast-moving collage of Chapman’s iconic black and white stills of our inhabitants, interspersed with Elliot Rudie’s colorfully animated drawings of the characters and settings, add an irresistible charm for the viewer. Melded with stylized dramatic reenactments by a troupe of actor look-alikes, it is easy to fall like Alice, into this make-believe world made real again.

The camera plays tricks with light and shadow, covering the character of Gregory Corso in a growing burst of smoke as the narrator describes his diminishing poetic powers. Burroughs remains a haunting, ghost-like figure throughout the film, disappearing at one point into the foggy landscape of the night. As Burroughs himself was often characterized as a sullen, non-verbal, father-figure to his ragtag band of followers, the director has handled the portrayal well.

Not to be forgotten are other luminaries of the time, such as Brion Gysin, a British painter and performing artist, who along with Ian Sommerville created the Dreamachine while living at the hotel. This was a whirling kind of lamp meant to produce hallucinatory dreams for the subject who would sit, eyes closed, in front of it. Harold Norse was obsessed with cut-up paper constructions, obviously inspired by the Dadaists of the day, which resulted in his novel, Beat Hotel. Another resident, singer/guitarist Peter Golding, is seen entertaining Madame Rachou and other residents with his lively rendition of “The Dark Town Strutters’ Ball.” A nicely-handled touch is a visit by Elliot Rudie to the present day Shakespeare and Company Bookstore, where he conducts a brief interview with the 95-year-old George Whitman, the former proprietor, in his bed.

Toward the film’s finale, a return visit occurs. A small group of onlookers watch as a brass plaque identifying the site as “The Beat Hotel” is placed on the exterior wall. Now the Hotel Relais (Le Relais du Vieux Paris), the building went through an extensive facelift in 1991, a tastefully baroque wallpaper covering a sampling of graffiti drawings left by former residents.

The Beat Hotel brings back the old bittersweet adage, “you can’t go home again,” but in Govenar’s sensitive production, for an hour or so, he lets us believe we can.

Govenar is also the president of Documentary Arts and the author of 18 books, including Texas Blues: The Rise of a Contemporary Sound; Stompin’ at the Savoy: The Story of Norma Miller, and Osceola: Memories of a Sharecropper’s Daughter (a first place winner in the New York Book Festival for children’s nonfiction). In tandem with the editing of Hatchett and the cinematography of Didier Dorant and Bob Tullier, he has created a passionate pastiche of the Beat generation for young and old alike.

“The Beat Hotel,” produced by First Run Features, opens at New York’s Cinema Village, 22 East 12th Street, on March 30, 2012. Running time is 82 minutes. For ticket information visit http://firstrunfeatures.com or call (212) 243-0600.