Benjamin Mack and the Box That Thunders

Deep in the heart of the southern African nation of Zimbabwe, there is a legend: a box-like object that the minority Lemba people claim can summon lightning, level mountains, and is instantly fatal to all those who touch it, except special circumcised priests. Known as the “Ngoma Lungundu,” or the “drum that thunders,” it is said to be empowered by the very voice of God.

Sound familiar? According to some, this object is the Biblical Ark of the Covenant, the box that stored the Ten Commandments given to Moses by God and the same thing that served as the McGuffin for Harrison Ford’s Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

And to a few believers, it’s at the Museum of Human Science in the Zimbabwean capital of Harare. Guess who couldn’t resist seeking it out?

Of course, there was the issue that I was in, well, Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe has the 15th-lowest Human Development Index (HDI) in the world; lower even than Haiti and Sudan, and street crime is a serious problem as visitors — especially Western ones — are frequently targeted due to the perception that they’re rich. With the average Zimbabwean earning a mere $589 per year, extreme poverty and starvation is a very real problem, as are diseases such as cholera, malaria and HIV/AIDS. Then there’s the fact that the country’s leader, 90-year-old Robert Mugabe, has ruled with an iron fist since Zimbabwe gained independence from Britain in 1980. Known to frequently drive around the capital, vehicular manslaughter is not unheard of as his aggressive motorcades snake through the streets. Long story short, he’s not the friendliest of autocrats.

But the lure of the Ark proved too strong — as did a number of “firsts” in this reporter’s seemingly permanent wanderings. Among those: First time in Africa, first time south of the Equator, and first in a country not named the United States or Canada where English is an official language.

Touching down at Harare International Airport via a nonstop flight from Amsterdam, the first word that popped into my mind upon surveying my surroundings was “decay.” Once one of Africa’s busiest airports — offering flights as far afield as Australia and the United Kingdom — barely 600,000 passengers now travel through Zimbabwe’s primary international gateway a year, with numbers continuing to decline. Hotels, consequently, have gradually fallen into disuse, with just a few dozen now serving the entire city of over 1.6 million. A large part of the issue is horrendous economic mismanagement, which led to a historical world-record inflation rate estimated at a mind-boggling 6.5 sextillion percent in mid-November 2008. The utter collapse of domestic markets led Zimbabwe to abandon its currency in 2009. Half a decade later, the US dollar is used almost exclusively.

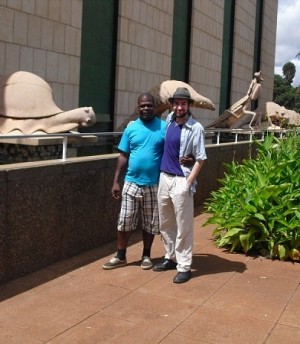

Hopping into an old white Datsun SUV after meeting my driver Mbafana, a friendly man with a deep voice who looked like he’d have a great career playing rugby or in the NFL, to say the road was littered with potholes would be an understatement. I’d spent a fair amount of time in rural North Korea — areas about as close to the Stone Age as one can get in the world today — and even there the roads are in better condition than this was. B-b-b-b-b-u-u-u-u-m-m-m-m-m-p! It was worse than severe air turbulence. Days earlier, the Zimbabwean government had signed a $400 million deal with a South African company to upgrade roads. I could only hope future visitors would be treated to less whiplash-inducing conditions.

The fact that it was late winter back at my home base in Germany meant it was late summer here, though temperatures in Harare — known as Salisbury until 1982 — vary little throughout the year. That said, it was still invigoratingly warm, the kind of warmth I hadn’t felt since a trip to Oman five months previously; I’d forgotten how much I preferred the heat over the chill of northern Europe.

Reaching the corner of Fife Avenue and Ninth Street, we pulled into the Small World Lodge, an outfit that caters to backpackers and other would-be adventurers. At a mere $12 a night for a dorm bed, it surprisingly is not the cheapest accommodation in town — nor the sparsest — but it had all that I needed: a bed and a pillow. The outdoor shower (lovingly called the “banana shower” by staff) nestled among the fluorescent green palms was a fun touch that, were this Europe, would give one hypothermia within seconds. But this was Africa.

My journey thus far had left me exhausted. “It’s not the years, honey. It’s the mileage,” Indiana Jones once said before passing out on a boat after one of his usual swashbuckling adventures. I slept soundly, knowing that, come morning, I would have a date with destiny.

The question of what happened to the Ark of the Covenant has fascinated theologians and archeologists for centuries. Its location is last mentioned in the Old Testament where, in the 18th year of his reign, King Josiah ordered the caretakers of the Ark to return it to the temple in Jerusalem (2 Chronicles 35:1-6; 2 Kings 23:21-23). Some 40 years later, the Babylonians captured Jerusalem and raided the temple. The Ark is never directly discussed in the Bible again.

But there are other potential sources that shed light on the Ark’s fate. The Apocryphal 2 Maccabees 2:4-10 (written around 100 B.C.) says the prophet Jeremiah, “being warned by God” before the Babylonian invasion, took the Ark and hid it in a cave, informing his followers that it should remain hidden “until the time that God should gather His people again together, and receive them unto mercy.”

The Maccabees story is where the Lemba legend picks up. According to them, a clan known as the Buba took the Ark to Africa for further safekeeping, spiriting it through present-day Yemen along the way. But God became angry, and the Ark self-destructed. Using a core from the original, Lemba priests then constructed a new one.

So how did the object purported to be the Ark come to the Museum of Human Sciences? It was discovered in a cave by Swedish-German missionary Harald von Sicard in the 1940s. Decades later, it was radiocarbon dated to roughly 1350 A.D. which, interestingly, coincides with the sudden and mysterious end of the Great Zimbabwe civilization, the most powerful empire known to have existed in Sub-Saharan Africa before colonialism. British officials originally put the vessel on display at a museum in Zimbabwe’s second city (but cultural capital in the eyes of some), Bulawayo, before it was transferred to Harare. It’s been in its present location ever since.