Artist of the Week 2/13-2/19: Lalage Snow Gives a Voice to the Faces Behind the War

Editorial Note: Due to the immense interest in this subject matter, we have included a few more questions than per the section’s standards.

“Everyone’s got a story to tell.” So says Irish born documentary photographer, Lalage Snow. As political as it is personal, Snow’s body of work alludes to traces from her past while giving a voice to militia men and women serving in the Middle East. Snow’s own father was a soldier, so she lived out the transience most any military family does — moving back and forth between Hong Kong and London, and then settling in Frankfurt before attending an all-girls school in South Kensington, London. After studying Ancient History and Classics at the University of Bristol, which Snow mentions “taught me that human nature changed very little over the centuries,” she realized journalism as a professional interest.

A one-year editorial assistant stint at a British wine magazine left Snow bored, and she quickly found a three-month newspaper writing internship in Bangladesh, followed by a six-month research job in Buenos Aires, until she decided “it was time to be grown up, get a proper job, you know, the normal stuff that my peers were doing.” Working for an estate agent doing public relations was miserable from day one, “it seemed like a hell of a sacrifice for a life I wasn’t sure I really wanted,” she says. Snow started freelancing for a Jordanian art and fashion magazine that offered her a job in Amman. And it was there, in 2006, that she not only finally realized it was possible to be a photographer full-time but also that photography is “where my heart, or at least part of it, lay.” Snow returned to the United Kingdom to earn a master’s degree in photojournalism and documentary photography.

Not surprisingly, the combination of Snow’s international travel and formal history education, i.e. her profound relationship to the experience of places and concept of time, has proven essential to her subsequent photography career. Snow does not simply consider herself to be among, with, or around her subjects, but instead, very thoughtfully uses the word “embedded” to describe her documenting efforts. Her fascination with combat is perhaps most emotionally depicted in her recent We Are The Not Dead series, which captures both the physical and emotional scars incurred by soldiers from the beginning, middle, and end of their service by exclusively photographing their faces. Viewers are challenged to compare and contrast the minute shades of difference distinguishing the same face as it changes over time. Besides physical features and expressions, lighting, and subsequently also, mood seem to shift between and within subjects’ triptychs. Using testimonials from her subjects, Snow provides a context from which a greater significance and understanding may be drawn and understood to inform her images.

Setting her camera down for a few brief moments, Snow takes us into the inner depths of her work and the emotions painted behind the faces of We Are The Not Dead.

GALO: How did your photography practice begin, and how has it changed in aesthetic and form from when you began?

Lalage Snow: I was given a camera when I was 14 and spent most of my free school time in the darkroom. I’d been taking photographs throughout my journalism jobs, but it was in 2006, when I was freelancing for a Jordanian magazine in Amman, that I decided to seriously pursue photography. I went on to study photojournalism and documentary photography at London College of Communication. Prior to that, my photography had been more abstract and less about people, and more just about mucking around with textures and reflections and having fun in the darkroom, so it was a bit of a change and forced me to do things I’d never have considered doing, but here we are today. I loved my undergraduate degree and still read the set texts like a proper geek.

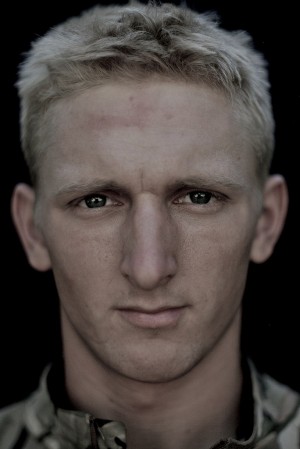

Second Lieutenant Adam Petzsch, 25. Photo and testimony courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

First image: “I suppose I am a bit apprehensive, but I want to see what it is really like.” Second image: “It was my first IED incident and first casualty. You don’t think about it till afterwards though, as your priority is getting the guy away and getting your guys back into safety. Then you start thinking about what happened, if it was preventable, if it was your fault in any way and how the others are doing. Before we were on this op, I was thinking about how quiet the tour had been and that we had to be careful and fight complacency. You have to be careful what you wish for.”

GALO: What was the basis of your interest in photographing soldiers’ faces for the We Are The Not Dead series?

LS: If writers are encouraged to write about what they know, perhaps the same is true for photographers. It was something I thought about in 2007, after my first embedment with British troops. I had gotten to know them before they deployed, and when I caught up with them three months later, I was met with gaunt, sunburned, bearded faces that I barely recognized. At the time, there was a lot of portraiture of soldiers on the ground looking tired, heroic, dirty or haggard, and I realized that the real story is in the way the faces changed — from boy to man, innocence to experience, etc. Also, a lot of boys were coming back in body bags or with missing limbs. The standard line on the news (for those who had died) was always, “He was an exceptional soldier,” or “he was well liked by his colleagues…,” etc. But I wanted to get to know the individuals.

As with most of the things I do, it took me another two years to actually put it into action. I also wanted to embed with the Afghan National Army, as they’re viewed as the white knight for foreign forces, and yet are still lacking resources and training. So I approached the UK MOD with a “double hit” to embed with a British Battalion who would be working hand in hand with an Afghan one.

Fortunately for me, some of the battalion had been in Iraq when I was embedded there in 2008, and so they knew me already. I spent three months with them on training exercises in the UK, which meant that they got to know me as much as I got to know them; they got used to me being around all the time with a camera. And most importantly, it meant that three months later, arriving in Helmand province, the guys knew me and were happy to talk about their experiences intimately. When it came to going out on operations, they knew that I was fit enough and happy to pull my weight.

Private Dylan Hughes, 26, Roxburgh. Photo and testimonies courtesy of: Lalage Snow.

First image: “I am not afraid of going out but AM afraid of fucking up and someone else dying. I am going to miss being able to do what I want, when I want.”

Second image: “After the IED: I was stunned. I thought it was one of us killed. And then we were contacted by Taliban snipers. It wasn’t a nice feeling. Not nice at all. This operation is the most dangerous thing I have done in my life. I was scared – not about what was going to happen to me but about the boys. It makes you think, it could have been me. It is just luck at the end of the day when it comes to IED’s. We are only three days into this operation and it feels like a lifetime – we are constantly under fire, and then there is basic living, which is difficult. It is what I enjoy in the army though, but I think even I will be at breaking point soon though.”

(Article continued on next page)