The Essence of Contemporary Today

“What makes this work contemporary?” is a question I went to the 2012 San Diego Contemporary Art Festival prepared with — an effort to extract the essence or principles behind what we call “contemporary art,” from which the festival gleaned its name — especially at a time when it seems anything goes and you’re prone to cock your head and go, “Is this art?”

But based on some of the responses from artists and their representatives, it seemed a bit like asking what makes water, wet (because… it’s water).

Ben Strauss-Malcom, director of the Quint Contemporary Art Gallery, summed it up — “Simply put, Mel [Bochner] is a living artist, contemporary artist. It was made this year, so that makes it very contemporary.”

Though seemingly otherwise, it’s not a question of semantics. “Contemporary” as a term is extremely flexible — applicable across all time periods, that which coincides with the “here and now” — an ever evolving status quo.

“Contemporary” is conveniently ambiguous for an era still in progress, with room for new voices and visions. It’s open ended, a time when it seems like anything goes, as was evident at the 2012 San Diego Contemporary Art Festival on September 6-9 at the scenic Balboa Park, arts and culture capital of San Diego.

After all, “contemporary” reaches beyond established norms, pointing to the future — sabotaging the rigid automation that may define how we live our lives in a world whose diverse transactions are increasingly automated.

This manifests as shock value, which momentarily suspends. It makes you pay attention. It begs questions.

And luckily some of the artists and those representing them were gracious enough to answer some of mine. Though they may not have the answers to humanity’s most pressing inquiries, they know that a train of thought fueled by additional brainpower gains momentum on its quest for resolution.

Society as a Black Hole

As I wandered about the festival, my eye naturally trained toward beauty and symmetry. We’re drawn to harmony and design — sometimes too much, as in the case with technology — especially in the age of Apple.

Artist Yim Choon Lee’s “Black Hole.” Photo courtesy of Katherine Kim.

Artist Yim Choon Lee “thinks that this society is like a black hole,” Katherine Kim said, who represents the artist and his work. “Society is pulling all of our identities and our personalities.”

Like the powerful dark forces in our universe that grow in size by absorbing nearby matter — from which nothing can escape — Kim describes a contemporary society that Lee sees as dehumanized due to industrialization and dependence upon technology.

Lee simulates his “black hole” by carving long gashes onto his canvas in a sun-like orientation, twisting each strip of fabric to reveal surges of color underneath. It’s like a brilliant wall of energy engulfing a foreign cluster — an intricate design that took shape through his observations of bamboo art and how it grows in nature.

“He wishes that our society is more together, more humanized, more [like] nature,” Kim said.

Lost Childhood

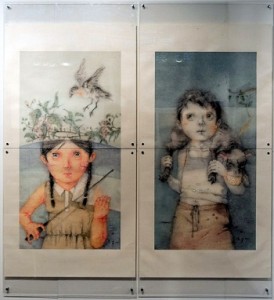

According to Chinese artist Zeng Jianyong, children growing up in modern day China are falling down that “black hole” much earlier than the rest of us.

We uphold childhood as sacred in its vulnerability and innocence, a condition also characterized by magic and wonder regarding the surrounding world.

Therefore, it’s unnerving to see images of downtrodden children and in the case of Jianyong’s Header series, presented in a creative fashion — as opposed to documented objectively as through a photojournalist’s lens obligated professionally to capture the world’s grim realities.

In China, a “header” refers to a child at the top of his or her class in academics and their ability to get along with teachers and classmates — a status that Chinese children aspire toward.

Despite their success, Jianyong’s “headers” are frigid in countenance, void of the rosy glow that often characterizes pride in achievement. With skin marred by gashes and swollen patches, they resemble child zombies — mutilation betraying an underlying narrative that obliterates the silver lining associated with accomplishment.

It’s a loss of childhood as a result of severe competition and pressure to perform — a phenomenon that according to Yan Liu, who organized the Chinese art delegation to attend the fair, has really come to bear in China within the last 20 years.

(Article continued on next page)